Vandenbroeck 2009

“Meaningful Caprices. Folk culture, middle-class ideology (ca 1480-1510) and aristocratic recuperation (ca 1530-1570): a series of Brussels tapestries after Hieronymus Bosch” (Paul Vandenbroeck) 2009

[in: Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, 2009 (published in 2011), pp. 212-269]

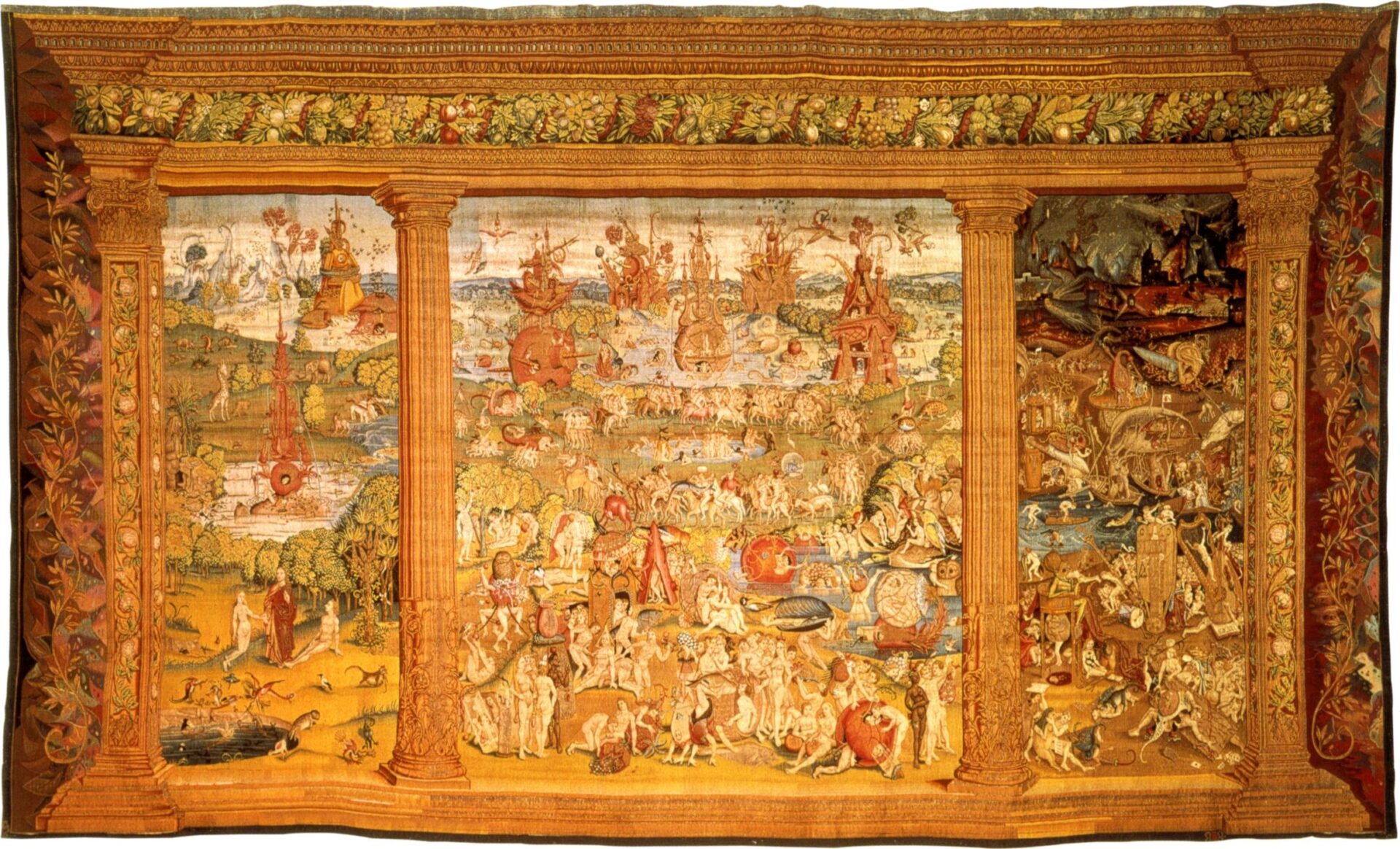

Today, the Spanish Patrimonio Nacional owns four tapestries ‘after Bosch’. The subjects are: St Martin and the beggars, The Temptations of St Anthony, The Haywain, and The Garden of Delights (a mirror copy of the original in the Prado). Apparently, the only reason why these four tapestries make up a series is because they all represent Boschian themes, which makes them unique. We know of three sixteenth-century owners of a similar series, to which a fifth tapestry representing The Battle Elephant also belonged: the French king Francis I, the Cardinal of Granvelle, and the Duke of Alva. In the first part of this contribution, Vandenbroeck elaborately focuses on the iconography of the five tapestries (including The Battle Elephant, which is known to us in other versions). This offers the author the opportunity to reiterate numerous of his earlier insights into Bosch (written in English and thus aiming at an international public). Noteworthy is that Vandenbroeck here suggests that Bosch painted the Garden of Delights triptych for himself, maybe on the occasion of his marriage in 1484. Some years later, in his monograph Utopia’s Doom, the author clearly came back from this idea (see Vandenbroeck 2017).

In the second part, Vandenbroeck deals with the history of the Spanish tapestries. He concludes that most likely they are the tapestries that were owned by the Cardinal of Granvelle and which were sold by his heirs to Emperor Rudolph II. In which way the series was moved from Prague/Vienna to Madrid in the seventeenth century is not known. The author also argues that the tapestry of The Garden of Delights was not copied after the original but after a copy, probably the copy that was owned by the Comte de Pomereu in Paris some years ago (and by a Geneva art gallery in 2022). Note 169 (pp. 264-265) sums up a number of details of the central panel where this copy and the tapestry together differ from the original. It should be noted, though, that a detail in the lower right corner (the plants above the heads of the three people in a cave) can be seen in the copy, but not (no longer?) in the original and in the tapestry. In the original it is clear that this detail has been retouched.

Hidden in another note (2, p. 214) can be found a concise and handy summary of Vandenbroeck’s view on Bosch literature, which at the same time explains how Bosch should be approached according to Vandenbroeck. I quote this note in full…

'The work of Hieronymus Bosch has been the subject of many international studies and publications in different languages. These studies are, in spite of their authors’ best intentions, often superficial and predictably biased from a linguistic and cultural perspective. In this context, it is worth emphasising the necessity of, first and foremost, research at different levels and pertaining to different layers of late-mediaeval European culture; equally indispensable is detailed regional research that takes into account all folkloric, iconographic, legal-historical, religious-historical and ideological-historical elements (in what follows, frequent reference will be made to very local publications); third, insight is required into Bosch’s visual language; and fourth, due account must be taken of the anthropological and cultural-historical context.'

[explicit July 6, 2024 – Eric De Bruyn]