Koldeweij 1991

De ‘Keisnijding’ van Hieronymus Bosch (A.M. Koldeweij) 1991

[Clavis Kleine Kunsthistorische Monografieën – part 11, Walburg Pers, Zutphen, 1991, 32 pages]

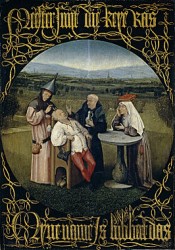

In the Bosch gallery of the Madrid Prado, rather inconspicuous next to the Haywain and the Garden of Delights, the visitor can see a small rectangular panel with a round oil painting in it. A quack with a funnel on his head is cutting away a flower from the head of a boorish fat man. Next to these two a monk is standing with a pitcher in his hand and a woman who is leaning on a little table is balancing a closed book on her head. If you are somewhat familiar with late-medieval literature and culture, you immediately understand this is a depiction of a keisnijding (cutting of the stone): texts and illustrations from that period regularly deal with the idea that stupidity and folly are caused by a pebble or stone in the head and that this handicap can be removed by means of an operation. This interpretation is confirmed by the calligraphic text surrounding the tondo: Meester snyt die keye ras / Myne name is lubbert das (Master, quickly cut out the stone / My name is Lubbert Das). Apparently these words are being spoken by the ‘patient’ who is tied down to his chair. Remarkable, but up to now invisible in the literature about Bosch, are the brushstrokes (called cadelures) that are lain crossways and that adorn the inscription. In 1987 Roger Marijnissen wondered why these cadelures had not been studied yet, although according to him they could be important for the dating of the painting.

Koldeweij has taken Marijnissen’s observation to heart for in a thin monograph (unusually thin compared to other books about Bosch) he tries to put the cadelures on the Cutting of the Stone panel (which, referring to Unverfehrt 1980, he considers to be a copy of about 1520 of a Bosch original) in their historical context. He relates the gothic ornamental letters of the inscription and the cadelures to similar calligraphic ornamentations on the name-boards and escutcheons that were painted by the Bruges artist Peter Coustens (better known as Pierre Coustain, the official court painter of the Burgundian dukes) for the fourteenth Chapter of the Golden Fleece, which took place in ’s-Hertogenbosch in 1481. Koldeweij assumes that the cadelures could also be seen on the Bosch original which leads him to the (carefully phrased) hypothesis that Bosch painted his panel under the influence of or perhaps in cooperation with Peter Coustens (who was staying in ’s-Hertogenbosch for a while in 1481). The painting could then be dated ‘1481’ or in any case shortly after that year. The commissioner of the later copy (identified by Koldeweij as the panel that is now in the Prado) was probably the bishop Philips of Burgundy (an illegitimate son of Philip the Good). According to inventories from 1524 and 1529 he owned a painting depicting Lubbert Tas die men die keye uyt snyt (Lubbert Tas who is being cut from the stone).

When comparing the four escutcheons that are depicted in Koldeweij’s book (two of them can be admired in colour in the exhibition catalogue In Buscoducis 1450-1629, p. 107) with the Prado panel, one has to admit that the similarity of the calligraphy and of the division of the surface is indeed striking. But there are also differences: one only has to compare the capital M, occurring twice in the Cutting of the Stone text (Meester / Myne), with the M on the escutcheon of Jehan de Melun. It follows that before being able to conclude that Peter Coustens was the executor of the Cutting of the Stone calligraphy, we should first have more material for comparison at our disposal. Because of this Koldeweij’s alternative hypothesis (the Prado panel was influenced by Coustens) seems more attractive for the time being, all the more so because the Golden Fleece escutcheons have stayed in the ’s-Hertogenbosch St. John’s until the end of the eighteenth century and we know from an archival document that in 1503/04 Bosch’s knechten (assistents) made escutcheons for three specifically named gentlemen. Perhaps one of these assistents was specialized in the painting of cadelures? Koldeweij points out that the calligraphy on the Cutting of the Stone can be related to a French-Flemish tradition that existed from the beginning of the fifteenth century up to the late sixteenth century [p. 12]. According to him Peter Coustens would have introduced this tradition to ’s-Hertogenbosch but in fact Hieronymus Bosch may also have become familiar with this tradition elsewhere. All this of course assuming that the Prado Cutting of the Stone can indeed be traced back to a Bosch original, for according to many Bosch scholars this is not sure, only probable.

Dating and authorship are not the only problematical aspects of the Prado panel. That the quack is not cutting away a stone but a flower from the head of Lubbert Das was explained as a pun by Dirk Bax: around 1500 the Middle Dutch word keye (stone) could also mean ‘carnation’. But the interpretation of the proper name Lubbert Das, of the monk with the pitcher, of the woman (or nun?) with the book on her head, of the funnel on the head of the quack, of the pitcher dangling from his belt and of the insignia with the little flower on his right shoulder: these are all problems Koldeweij touches upon but for which the literature about Bosch hasn’t found an explanation yet. Regarding the name Lubbert Das Koldeweij refers to the meaning of ‘castrating’ the verb lubben could have and to the fact that lubbert could be a man’s name as well as a synonym for ‘stupid, foolish person’. Lubbert Das may have been derived from the latin form Lubbertus. And in the Antwerp dialect of the nineteenth century zo vet als een das (as fat as a badger) was a common expression [pp. 9-10].

Apart from the Prado panel Koldeweij also pays attention to a number of free imitations of another Cutting of the Stone painting (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum) that is sometimes attributed to Bosch, to the Cutting of the Stone paintings that were owned by Philip II and archduke Ernst of Austria, and to depictions of the same motif by Bruegel, Maerten van Cleve and Peter Balten [p. 8].

Reviews

[explicit]