Snyder 1980

Hieronymus Bosch: The Man and His Paintings (James Snyder) 1980

[Ferndale Editions, London, 1980, 133 pages]

[Also mentioned in Gibson 1983: 13 (A63)]

Bosch is said to have been a good Catholic and definitely not a member of some occult sect. A number of documents prove that he was a member of the pious Confraternity of Our Lady. We also know a number of Bosch’s collectors and patrons and they were mainly aristocratic Catholics. His art was further influenced by the mystics (in particular by Ruusbroec) and by the Modern Devotion. The major theme of the Modern Devotion was solitary, contemplative life. The desert-hermits were the big example and precisely these hermits and recluses were depicted by Bosch more than once.

When in the sixteenth century the role of the Church as a patron of the arts began to decrease its function was taken over by intellectual nobility and rich middle class and the new subjects introduced by Bosch into religious imagery appealed to these social layers. In his paintings Bosch clearly presents himself as a moralist: he paints satires on sinful humanity and in doing so he seems to have a rather pessimistic opinion of man. Bosch must be situated within his contemporary social and religious context and seems to have a certain degree of esoteric knowledge. This does not mean that Bosch wàs a magician, wizard or alchemist, but he was aware of these things, which is an important distinction. A number of Bosch’s in-laws were pharmacists and that is how Bosch may have been informed about alchemy and related things. This latter statement is erroneous: the archives tell us that only the great-grandfather of Bosch’s wife was a pharmacist (see Van Dijck 2001a: 45 / 158).

Snyder also focuses on Bosch’s style. Bosch’s style is said to agree more with the North Dutch than with the Flemish school, although he is too unique in order to belong to a school. Bosch also invented a new technique of painting that perfectly matched his pessimistic view of the world: the spontaneous and incoherent scattering of figures across the panels, the often semi-transparent pastel colours and the quick, sketchy execution give the figures a spontaneous and dynamic character and the setting a fluid appearance that effectively expresses the painter’s vision of a turbulent, illusionary world peopled by sinners who blindly race about toward all kinds of foolish things. His approach of landscapes was original as well, with its shifting tonalities (the background blue-grey, the foreground in darker, local colours).

A recent hypothesis mentioned by Snyder is the suggestion that Bosch was left-handed. This can be deduced from the underdrawings that can often be seen through the paint layers of his generally accepted works. As already stated above, Bosch’s execution was quick and sketchy (in his Schilder-Boeck Karel van Mander already signalled this) and that is how a manner of shading was revealed with parallel lines that move from the top left to the bottom right: the natural movement for someone who draws with his left hand. According to Snyder this is an important discovery: if more of these stylistic characteristics can be revealed we would have a number of reliable standards to sort authentic drawings and paintings out from imitations.

Further, Snyder stresses Bosch’s pessimism. Why was he so interested in painting Hell and the Last Judgment? Snyder relates this to the turbulent age in which Bosch was born: this age was obsessed with apocalyptic warnings of the destruction of the world, a fear that had already appeared in Europe at the end of the fifth and tenth century in the shape of millenarianism (the fear of the year 1000). With the approaching year 1500 a similar wave of fear and pessimism began to spread and Snyder suggests that this is the cause of Bosch’s renewed success today (A.D. 1980). On the eve of the year 2000 the medieval millenarianism pops up again in the shape of doom-mongering (Third World War, nuclear annihilation of life on earth). And it was exactly this apocalyptic fear that Bosch painted, as some sort of early fifteenth-century doom-monger.

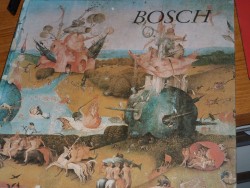

A lot about the Garden of Delights can be explained if we turn to the Bible and its comments. Moreover, the triptych is the traditional form of the Last Judgment altarpiece and this fact gives us important clues as to Bosch’s intent. Obviously, it is a warning of Luxuria, but when it comes down to interpreting the central panel Snyder agrees with Gombrich: this panel represents sinful mankind in the days of Noach, immediately before the Flood, and the correct name of the triptych might be Sicut erat in diebus Noe.

Snyder is a good example of the modern, right-minded Bosch scholar. His ideas agree with the ‘moderate’ majority and his approach is an average of what was known about the life and art of Bosch A.D. 1980. His book is definitely to be preferred to the French 1977 version with the same illustrations but with a text by Claude Mettra, who does nothing but double the problem by writing about Bosch’s enigmas in an enigmatic way.

[explicit]