De Vries 1964

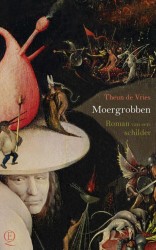

Moergrobben (Theun de Vries) 1964

[Novel, P.N. van Kampen, Amsterdam, 1964]

[2nd edition: Theun de Vries, Het raadselrijk. Em. Querido’s Uitgeverij B.V., Amsterdam, 1973]

[3rd edition: Theun de Vries, Moergrobben – Roman van een schilder. Em. Querido’s Uitgeverij B.V., Amsterdam-Antwerp, 2016, 372 pages]

[German translation: Theun de Vries, Die drei Leben des Melchior Hintham – Ein Malerroman. Henschel-Verlag, Berlin, 1966]

[Not mentioned in Gibson 1983]

The protagonist of this historical novel is the late medieval painter Melchior Hintham, a manifest double of Jheronimus Bosch: his main skill is the painting of ‘moergrobben’ (devils and infernal creatures), he is a close friend of the architect Kiliaan Bor (= Alaert du Hameel) who is constructing the St Andrew’s church (= St John’s), he is in contact with the Grand Master of the heretical Adamite sect (Charles van den Caudenberg = Wilhelm Fraenger’s Jacob van Aelmangien) and his iconographical themes are very similar to those of Bosch (only The Cutting of the Stone is literally mentioned but also in this case the final execution is clearly different from that of Bosch’s panel).

Obviously, a book like this is of little worth for the scholarly study of Bosch: De Vries (1907-2005) turns Hintham/Bosch into an introverted, marginal figure, his wife (Kiliaan Bor’s daughter) leaves him for the Adamite Grand Master, he strongly clashes with the religious leader of his Brabantine hometown (deacon Franciscus Kals), he adopts a poor vagabond (Tetje Roen) as his servant and when he is older he falls in love with the nun Amanda, a love affair with a deeply disappointing ending (Amanda’s superiors send her to another monastery).

At the end of his life, Melchior loses his faith in hell and heaven and during an in-depth conversation with duke Philip the Fair (who is visiting Hintham’s workshop to commission a Last Judgement) he explains why he does not paint ‘moergrobben’ anymore: these were meant as satirical comments on man’s sins and now Hintham does not paint them any longer because of ‘his hope and expectation for a less monstrous mankind’ [3rd edition, p. 338]. At that moment Melchior realises the ‘outcome of his own life’: ‘The big change could only be brought about by the people themselves’ [ibidem]. A point of view that was more than probably inspired by the Marxist ideas of author Theun de Vries. The continuous criticism of worldy and religious leaders in the novel points in the same direction. ‘Because almost half of De Vries’ books deal with artists, he mainly described inner conflicts in which highly talented, genial persons may find themselves because of their spirit of freedom,’ Eberhard Hilscher wrote in a 1977 article. Indeed, this ‘freedom’ motif also plays an important part in Moergrobben: during the conversation with Philip the Fair Hintham realises that he has more freedom than the duke, who is bound by protocol and ceremonies: ‘He, Melchior Hintham, was free, the conclusion amazed him: he had more freedom than anyone he knew’ [3rd edition, p. 339]. The novel’s last sentence reads (old man Melchior is sitting in his autumn garden): ‘Then he tasted a salty flavour of freedom on his face and tongue, driven towards him by dusk and the westerly wind, but he had no name for it’ [3rd edition, p. 372].

As a Bosch novel Moergrobben may not amount to very much, as a novel as such it is a praiseworthy piece of work, but not a masterpiece. De Vries’ writing skills are obvious. Remarkable are his sparing use of dialogues and the fact that he excells in long and yet compelling epic depictions of his subject matter, as was also noticed by Hilscher [1977: 429]. Another characteristic of his style in Moergrobben is the frequent use of ‘odd’ words. The title (impossible to translate, in English it could be something like ‘marshmongrels’) is a good example of this and other examples abound. By using these ‘old-fashioned’ words, De Vries probably wanted to evoke the spirit of the Middle Ages.

One of the reasons that Moergrobben has not become a masterpiece is the poor incorporation of the ‘heretical Adamite sect’ motif into the novel. Hintham meets the Grand Master of the sect a few times (he visits Hintham in his house and even seduces his wife) but he never participates in any of the sect’s sessions (with nudism and free love on the menu). And in spite of the fact that Hintham keeps his distance, he seriously clashes with the religious leaders of his town. They even engage a Dominican inquisitor but after this monk has died in a city fire, Melchior (who makes no effort at all to get in touch with the sect after the ‘kidnapping’ of his wife) is not troubled anymore. ‘The function of the heretical sect theme in the novel is not very clear,’ Hilscher [1977: 431] also noted.

In 2016, a new, third edition of the novel was published (again using the original title Moergrobben, the title of the second edition was Het raadselrijk – The Land of Enigmas), no doubt because in 2016, 500 years after the painter’s death, Bosch received a lot of attention, with two important exhibitions, one in ’s-Hertogenbosch and one in Madrid.

Literature

[explicit 21 May 2017]