Fraenger 1947

Das Tausendjährige Reich: Grundzüge einer Auslegung (Wilhelm Fraenger) 1947

[Winkler, Coburg, 1947, 142 pages]

[Reissued in: Wilhelm Fraenger, Hieronymus Bosch. Prisma-Verlag, Gütersloh, 1975, pp. 9-144]

[Also mentioned in Gibson 1983: 88 (E91)]

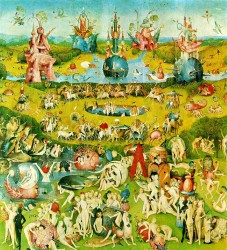

In this book, which is integrally allotted to a profound analysis of the Garden of Delights triptych, Fraengers starting-point is the observation that Bosch’s oeuvre comprises two different kinds of painting: on the one hand a group of altarpieces and devotional panels with a very enigmatic content, on the other hand a group (with i.a. the Passion scenes and the Adoration of the Magi motif) in which the enigmatic symbols remain limited or are totally absent. These latter works are characterized by pious devotion whereas the former ones contain quite some satire on the Church, but also on mysterious cults.

According to Fraenger Bosch must have had two different patrons: the Church and a revolutionary opponent of the Church that belonged to pre-reformational circles and at the same time criticised (other) mysterious cults: in other words a sect. Very much at random Fraenger identifies this sect as the Brothers and Sisters of the Free Spirit, and more precisely as the Homines Intelligentiae or Adamites. According to an archival source dating from 1411 this sect was flourishing in Brussels (among other places) at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Fraenger does not explain how Bosch came into contact with this Brussels wing of the Free Spirit movement. Historical sources about the existence of a similar sect in ’s-Hertogenbosch are not extant, but still Fraenger is strongly convinced that Bosch – more or less in a hidden way – was a member of this sect and that the leader of the sect or ‘Supreme Master’ thoroughly instructed Bosch regarding the composition, message and symbolical ideas of the paintings he produced for the Adamites.

As long as Bosch did not cause any public offense, the Church kept ordering paintings from him. According to Fraenger this was typical of the confusing period of transition in which Bosch lived and worked. And this led to an oeuvre that consisted of both traditionally Christian and mysterious-sectarian panels.

The Garden of Delights triptych was a painting that (supposedly) had a function within the cult of the Adamite sect. It was meant to lead to meditation and could also be used for the instruction of new members. Fraenger sees the triptych as a kind of encylopedia of the vorreformatorische Sektenchristentum (pre-reformational sectarian Christianity): Bosch’s triptych is an important source for our knowledge about the Adamite sect, just as the panels of the Van Eyck brothers and of Lucas Cranach can be seen as elucidating summaries of the Catholic and Lutheran range of thought respectively. Although historical sources tell us very little about the Adamite sect, Fraenger deduces everything we did not know yet from Bosch’s triptych, and in doing so he turns the argumentation upside down: what had to be proven, is adduced as proof.

In a nutshell his interpretation boils down to the opinion that the left inner wing is an illustration of the eternal unity between God and man, whereas the central panel represents the ‘Paradise’ or ‘Thousand-Year Reign’: within the sect these latter terms implied that through the rejection of all awareness of sin and the purified experience of sexuality man in his earthly life could reach a higher degree of reality. The Hell on the right inner wing is interpreted in a figurative way. It represents the life (on earth) of those who have not yet implemented the ideas of the sect: adepts of the Catholic belief, children of the world (knights, mendicant people) but also members of the sect itself who have not yet been purified. According to Fraenger the head of the so-called ‘tree-man’ is a portrait of the Supreme Master himself, but this does not cause a problem: the sect believed that even the heaviest sinner could enter the Thousand-Year Reign after having been purified, so why not the Supreme Master himself?

The general outline of this analysis may sound appealing and well-thought-out, but Fraenger’s interpretations of details can only be read with a shake of the head. The two major objections against Fraenger’s assertions are that he often makes erroneous observations when describing what can be seen on the panels, and that his interpretations are largely far-fetched. In this context more arguments and examples can be found in Bax 1948: 297-305 (Bax 1979: 390-396) and Bax 1956: 135-148. Since research in the nineteen-sixties it has become highly probable that in 1517 the Garden of Delights was possessed by count Henry III of Nassau and that he or his uncle Engelbert II of Nassau was the patron of the triptych. There are no signals that these noblemen were in touch with any secret sects, which is why Fraenger’s sensational theories have become even more improbable than before.

[explicit]