Pinson 2010

“A moralized semi-secular Triptych by Jheronimus Bosch” (Yona Pinson) 2010

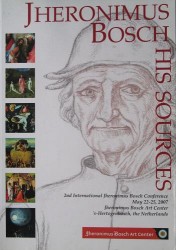

[in: Eric De Bruyn / Jos Koldeweij (eds.), Jheronimus Bosch. His Sources. 2nd International Jheronimus Bosch Conference, May 22-25, 2007, Jheronimus Bosch Art Center, ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands. Jheronimus Bosch Art Center, ’s-Hertogenbosch, 2010, pp. 265-277]

In this contribution Pinson focuses on the recently reconstructed triptych that consists of the Rotterdam Pedlar (closed wings), the Paris Ship of Fools and the New Haven fragment (left inner wing) and the Washington Death of a miser (right inner wing) and of which the central panel is missing. This ensemble of fragments shows analogies with other of Bosch’s outwardly semi-secular triptychs that were intended as moral lessons by revealing folly and sin. According to Pinson the pedlar on the closed wings is meant to be an image of the ‘homo viator’ at the crossroads and of the choice between right and wrong. This theme had a certain tradition in Bosch’s time but Bosch ironically inverts its original meaning, thus parodying the idea of human choice: in his view human choice is a priori motivated by man’s earthly desires and is bound to lead to death and perdition. Referring to a text by Bernard of Clairvaux Pinson associates the pedlar’s act of looking back over his shoulder with negative connotations.

The idea of a perpetual human choice between virtues and vices is reflected through the remaining panels of the dismembered triptych. For example, the emblematic opposition of foliated and bare branches (symbolizing good and evil) also occurs on the (reconstructed) left inner wing. This wing illustrates the submission of members of various strata of society to folly and sins, notably lust and gluttony. The concept of the universality of sinners seems to Pinson essential for understanding Bosch’s thought and ideology. The left wing should be read as a moral condemnation of the dissolute behaviour of both clergy and laity.

The deathbed scene on the right wing depicts the moment when angel and devil are battling over the dying man’s soul, but we cannot ignore that the dying man is clearly more enticed by the devil than by the angel. Again this reflects Bosch’s ironical reflection and pessimism. Although the central panel is still missing, Pinson presumes it could have depicted another moralizing semi-secular scene that would have completed the iconographical program of the Seven Deadly Sins.

With this last remark Pinson contributes to a specialism that was introduced to modern Bosch exegesis by Lotte Brand Philip in 1958: guessing what could be seen on lost Bosch panels no modern viewer has ever seen. The reader should also be reminded of the fact that since the 2001 Rotterdam Bosch Exhibition it has indeed become probable that the Rotterdam, Paris, New Haven and Washington fragments have once belonged to the same triptych, but the available data don’t allow us to call this a proven fact.

[explicit 3rd August 2012]