Benesch 1937

“Der Wald, der sieht und hört. Zur Erklärung einer Zeichnung von Bosch” (Otto Benesch) 1937

[in: Jahrbuch der Preussischen Kunstsammlungen, 58 (1937), pp. 258-266]

[Reissued in: Eva Benesch (ed.), Otto Benesch. Collected Writings. Volume II: Netherlandish Art of the 15th and 16th centuries – Flemish and Dutch Art of the 17th century – Italian Art – French Art. Phaidon, New York-London, 1971, pp. 279-285]

[Also mentioned in Gibson 1983: 129-130 (F4)]

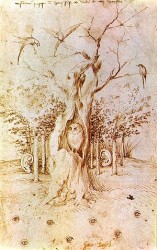

Benesch analyses the Bosch drawing with inventory-number 549 in the Berlin ‘Kabinett’. He gives the drawing the wrong title Der Wald, der sieht und hört (The wood that sees and hears). The correct title is obviously The field has eyes, the wood has ears. This mistake is all the more remarkable because Benesch links the drawing – rightly so this time – to the proverb the wood has ears and the field has eyes and to a Dutch woodcut from 1546 in which the proverb is represented.

Benesch reads the inscription – which according to him was written by the artist himself, in other words: by Bosch – as follows: Miserrimi quippe est ingenii semper uti in bestiis et nunquam iucundis. This sentence (= it is the characteristic of an unhappy spirit to always seek the company of animals and never friendly ones) is also expressed in a graphic way: birds are mocking an owl. The birds who are moving and squawking in an excited way, are exotic (perhaps macaws), the two silent birds are magpies. The motif ‘magpies in the neighbourhood of an owl’ is also present in the Bosch drawing The Owls’ Nest, which represents the proverb it is a real owls’ nest and in the drawing of the Treeman in the Vienna Albertina. This latter drawing does not represent a proverb but illustrates a late-medieval symbolic idea which is also present in a copper engraving by the Master of the Banderoles: the tree of life floating on the water in a little boat. This idea is also represented on Bosch’s Ship of Fools (Paris, Louvre).

The fox and the cock at the foot of the tree in the Berlin Bosch drawing also express the idea of enmity. Because the name ‘Bosch’ means wood in Dutch, the proverb that Bosch depicted had a special meaning for him: Bosch drew an eingekleidetes Selbstbildnis (disguised self-portrait). Bosch portrayed himself as a fox (compare with the proverb he has become a fox, he is hiding), as a wood, as a tree and as an owl. Perhaps Bosch thought of himself as being as melancholic as an owl. Bosch portrayed himself as an observer who watches the world from a distance and confronts the world with a mocking mirror.

It is quite obvious that this interpretation is confusing, superficial and not very convincing. Dirk Bax wrote about this article: ‘The listening wood is supposed to be Bosch himself. This could still pass but he sees the artist represented also in the eyes, the tree, the fox and the owl, which is unacceptable’ [Bax 1948: 162 (note 13) / Bax 1979: 209 (note 13)]. Furthermore, the correct reading of the sentence at the top of the drawing is: ‘Miserrimi quippe est ingenii semper uti inventis et nunquam inveniendis’ (for it is typical of a very miserable spirit to use other people’s inventions all the time and never to come up with something original) [see Vandenbroeck 1981a: 178].

[explicit]