Büttner et al. 2016

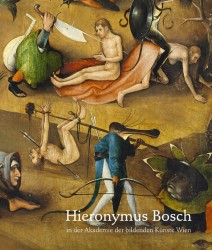

Hieronymus Bosch in der Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien (Nils Büttner, Julia M. Nauhaus, Erwin Pokorny and Larry Silver) 2016

[Verlag Bibliothek der Provinz, Vienna, 2016, 32 pages]

From November 4, 2016 until January 29, 2017 the Viennese Akademie der bildenden Künste organises (organised) the exhibition Natur auf Abwegen? – Mischwesen, Gnome und Monster (nicht nur) bei Hieronymus Bosch [Nature gone astray? – Hybrids, Gnomes and Monsters (not only) in the work of Hieronymus Bosch]. In the margin of this exhibition a small monograph (clearly intended for the general reader) was published on Bosch’s Last Judgement triptych (Vienna), with contributions by four authors.

In the short introduction Julia Nauhaus introduces the Viennese Akademie der bildenden Künste. We learn that today the Gemäldesammlung counts some 1,200 works whereas the Kupferstichkabinett owns some 40,000 drawings, 100,000 graphic works and more than 22,000 artistic photographs.

In Hieronymus Bosch und das Wiener Weltgericht [Hieronymus Bosch and the Vienna Last Judgement] Nils Büttner writes that most Bosch works deal with Christian themes. Because of the diverging size the Last Judgement triptych in Vienna cannot be the triptych that was commissioned by Philip the Fair from Bosch in 1504. In 1659 the triptych was part of the collection of archduke Leopold Wilhelm (who, as the Habsburg Stadholder, resided in Brussels from 1647 till 1656). That the triptych is not a copy becomes clear from the numerous changes in the underdrawing and during the painting process. One of the important changes can be seen in the coat of arms in the lower exterior right panel: the weapon has not been painted although it was planned in the underdrawing (unfortunately not clear enough in order to be identified). The identification of the saint who is represented in the exterior right panel also causes problems because the iconography of Saint Bavo, Saint Hippolyte, Saint Theobaldus and Saint Julianus is very much alike. Büttner rejects the hypothesis that the triptych was commissioned by Hippolyte de Berthoz (Jos Koldeweij’s hypothesis, although Koldeweij is not mentioned in the text) because of the donor who was planned in the underdrawing (lower left corner of the central panel) but not painted. Hippolyte de Berthoz had himself painted together with his wife in a triptych that was commissioned from Dirk Bouts and Hugo van der Goes circa 1475. If the donor of the Vienna triptych had been married, he would also have had his wife represented, because such a commission was – among other things – intended to receive less punishment in Purgatory (see further below, though).

In Ein einzigartiges Weltgericht [A Peculiar Last Judgement] Larry Silver points out two unusual aspects of the Vienna triptych. As opposed to the Last Judgement triptychs by Rogier van der Weyden and Hans Memling only a few good souls are directed towards Heaven in Bosch’s painting. In the upper left corner of the central panel Heaven has been represented in a very small and vague way. Unusual as well, is the left interior panel, dealing with the arrival of Evil into the world with the Fall of the Rebel Angels and the Fall of Adam and Eve.

In Wann hat Bosch das Triptychon gemalt? [When has Bosch painted the triptych?] Erwin Pokorny argues in favour of an early (earlier) dating of the Vienna triptych, although he admits this is only a hypothesis. In recent literature the Vienna triptych is dated circa 1500-1505 but it may as well have been painted 10 to 15 years earlier. Pokorny’s arguments are the following…

With respect to an early dating of the Vienna triptych the first, the fourth and the sixth argument can hardly be called conclusive. More important are arguments 2 and 5. Argument 5 presupposes Bosch’s influence on Du Hameel. But what if Bosch was influenced by Du Hameel, as has been suggested in De Vrij 2012: 319? Regarding argument 2 (the donor figure that was not painted in the final version): would it not be very unusual if a donor had himself represented amidst diabolical tortures and punishments? In other words: if this donor had effectively been painted, he would feel very unwelcome there! Could it not be possible that Bosch used an ‘old’ panel that was intended for another commission that was cancelled for an unknown reason? That would explain why the donor’s hat was out of fashion circa 1500 and it does not contradict the dendrochronological data. Of course, in that case the unpainted donor was not Hippolyte de Berthoz (the hypothetical commissioner of the Vienna triptych), which makes Pokorny’s and Büttner’s rejection of Koldeweij’s hypothesis irrelevant. That the Vienna triptych has not been signed obviously remains a fact but it can hardly be called a convincing argument either (the Garden of Delights also lacks a signature). How we have to interpret the dating that is used elsewhere throughout the book (‘started circa 1490, completed circa 1505’), remains a mystery.

In a separate short chapter the Vienna Hellship drawing is introduced. The book has some nice and clear illustrations. The suggestion that the sign on the giant knife in the central panel may be read as a ‘B’ or as an ‘M’ that stands for miserere (see the note accompanying illustration 30 on page 23) can duly be ignored: meanwhile, thanks to archival research by Lucas van Dijck (published in 2016) we know that this sign is a round ‘M’ functioning as the logo of the ’s-Hertogenbosch producer of knives Anthonius Jonckers. The Bosch Research and Conservation Project was denied access to the Vienna triptych but in this book we read nothing about the Akademie’s own research, apart from what is communicated about the coat of arms in the lower right exterior panel. That the (concise) bibliography does mention the highly irrelevant book by Cees Nooteboom but forgets to refer to Dirk Bax’s (English-written!) work of reference on the Vienna triptych (Hieronymus Bosch and Lucas Cranach – Two Last Judgement triptychs, 1983) is incomprehensible. An English version of the book reviewed here will be (has been) published in January 2017.

[explicit 20th December 2016]