Cat. Rotterdam 2015

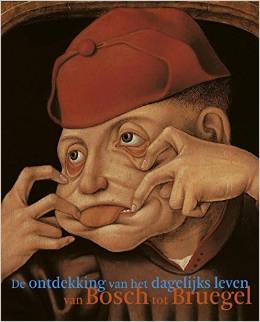

De ontdekking van het dagelijks leven van Bosch tot Bruegel (Peter van der Coelen and Friso Lammertse) 2015

[Exhibition catalogue, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (10th October 2015-17th January 2016), 2015, 287 pages]

This catalogue is not only written in a fluent and pleasant style but also lavishly illustrated and it offers a goldmine of information to the reader who is interested in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century iconography, in particular in genre art from the period 1500-1570. Although it was already present in fifteenth-century German and Dutch genre graphics (chapter 1), shortly after 1500 genre art (representing everyday life) was a novelty in the art of panel painting. Three painters, Jheronimus Bosch (chapter 2), Quinten Massys (chapter 3) and Lucas van Leyden (chapter 4) were the leaders in this field. Separate chapters are devoted to sixteenth-century Dutch and German genre graphics (chapter 5), to the Braunschweig Monogrammist and Herri met de Bles (chapter 6), to Jan Sanders van Hemessen (chapter 7), to Pieter Aertsen and Joachim Beuckelaer (chapter 8) and to Peter Bruegel the Elder and his environment (chapters 9 and 10).

The word ‘genre’ was only used as late as the nineteenth century to refer to an (apparently) everyday scene. Genre scenes focus on human figures in everyday situations and do not represent historical, Biblical or mythological events, but in this catalogue the notion ‘genre’ is interpreted in a very broad way. ‘Apart from “genre” in the strict sense this period offers depictions of proverbs, of unequal lovers and particularly of the world turned upside down, in which wives are bossing their men around. In these representations everyday subjects mingle with allegory, satire and morality’, we read on page 21. Therefore it sounds somewhat strange and even provocative when it is explicitly claimed elsewhere in the catalogue (i.a. on pages 22-23 / 25 / 51 / 141) that the primary intention of the prints and paintings discussed was not to convey a moral message and that the tone is often more humoristic than moralistic. It is a thesis that requires some time for reflection and perhaps even some due reservation.

Furthermore, the rise of genre art is related to the rise of the middle classes (p. 27) and to the religious changes influenced by the Reformation in the sixteenth century (p. 28). This catalogue also taught us some new words: a stokbeurs (literally: ‘stick-purse’, a stick with a number of purses attached to it, see i.a. p. 105), a puntneuskruik (literally: ‘pointed nose jar’, a jar with a little face on its frontside, see i.a. p. 198) and thematical inversion: the fact that the actual ‘main subject’ is pushed to the central part or background whereas the foreground shows everyday scenes (see p. 146, although the same phenomenon is called reversed composition on p. 194). Some minor criticism: a couple of times (i.a. on page 157) an oblieman (a travelling waffle seller who let his clients gamble for the wares he carried with him in a round vessel) is not recognized in the visual sources discussed. The articles Bernet Kempers 1973a and Bernet Kempers 1973b, which offer interesting information in this respect, are not mentioned in the catalogue’s bibliography.

Chapter 2, written by Friso Lammertse, is completely devoted to Jheronimus Bosch (pp. 54-71). Bosch is considered an early representative of Dutch genre painting, but this is only based on a very small part of his preserved oeuvre: the Rotterdam Pedlar tondo, the exterior panels of the Haywain, the scenes in the foreground of the Haywain’s central panel and the deadly sins scenes in the so-called Prado Tabletop. Lammertse points out (referring to Koreny 2012) that recently it has been suggested that these paintings should be removed from the list of authentic Bosch works, but he does not take a personal point of view in this matter. About the Haywain and the Pedlar he writes: ‘It is important that the scholars agree that if these two paintings are not by the master himself, they have been produced in his close environment by a workshop assistant’ (p. 55). Lammertse also points out that Bosch’s genre scenes are imbedded in an allegorical and devotional context and that not this global context, but details from it were largely imitated in the sixteenth century, by means of paintings with one clear subject. Bosch may have already created such little paintings but these have been lost (because they were often painted on canvas) or we know them only from (uncertain) copies, as is the case with The Cutting of the Stone (Prado), The Conjuror (Saint-Germain-en-Laye), The Dance of Carnival and Lent (i.a. Amsterdam) and The Repairer of Bellows (Tournai).

On pages 69-70 then follows an important sentence: ‘It is possible that the two triptychs [Lammertse is referring to the Haywain and the lost Pedlar triptych] are quite atypical examples of his art that have withstood time because of their more hard-wearing materials but offer only a weak reflection of the real contribution of the artist to the rise of a profane art of painting’. It is a statement that closely agrees with the writings of Paul Vandenbroeck. The statement in chapter 9 (written by Lammertse and Van der Coelen) that Bosch’s world is haunted by fear whereas Bruegel looks at man in a more mild and humorous way (p. 205) seems to echo the views of Roger Marijnissen.

On a few occasions Lammertse seems to agree a bit too easily with very recent findings of Bosch research. It is, for instance, remarkable that the saint in the right exterior panel of the Vienna Last Judgment triptych is not called St Bavo but St Hippolyte (in the wake of Koldeweij, though he is nowhere mentioned in this particular context). On page 75 (in another chapter, written by Van der Coelen) it is claimed that Bosch painted his Haywain circa 1515: the possibility that both Haywain triptychs we now know are late workshop replicas of an early Bosch painting is thus not acknowledged.

Furthermore, I am somewhat disappointed that on page 63 Lammertse does not choose in favour of a positive interpretation of Bosch’s pedlars: ‘That the pedlar in both paintings is old, does not seem a coincidence but which choice he will make at the end of his life remains uncertain’. With their stick (a topical reference to the support of good faith and Christ) the pedlars keep a harshly growling dog (a topical image of the devil) at safe distance: this means that what they are doing is okay (in spite of their earlier sins) and everything points out that they will make the correct choice. Moreover, without exception the exterior panels of Bosch’s triptychs basically show the good example. For the rest, nothing but praise and approval for this nice catalogue and for the exhibition it accompanies.

[explicit 6th December 2015]