De Bruyn 2016b

“The Iconography of the Lisbon Saint Anthony triptych: Bosch and the Vita Antonii” (Eric De Bruyn) 2016

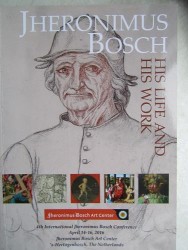

[in: Jo Timmermans (ed.), Jheronimus Bosch – His Life and His Work – 4th International Jheronimus Bosch Conference – April 14-16, 2016 – Jheronimus Bosch Art Center – ’s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands. Jheronimus Bosch Art Center, ’s-Hertogenbosch, 2016, pp. 56-65]

Recent literature has stressed two pivotal aspects of Bosch’s Lisbon St Anthony triptych: its Christocentrism and the fact that the four scenes showing Anthony were inspired by medieval legends about the saint, the sources being Athanasius’s Vita Antonii, the Passionael (Gouda, 1478) and the Vader boeck (Zwolle, 1490). Today, we have a relatively fair understanding of the basic message of the triptych and of the essential iconography of its four principal scenes, but the opposite is true for what could be called the triptych’s ‘secondary scenes’. Recently, there has been a modest tendency (Stefan Fischer, BRCP) to look for the iconographical key to these secondary scenes within the same medieval literary tradition that inspired Bosch when painting the four principal scenes. To grasp how Bosch may have been inspired by late medieval texts about St Anthony when painting the secondary scenes, a crucial difference between these secondary scenes and the principal scenes needs to be pointed out. In the four scenes showing Anthony the saint is being tempted in a physical way, by means of violent and sexual actions. In the secondary scenes the devils are creating diabolical illusions to disturb the saint in a mental way by enacting blasphemous and disparaging parodies of things that are precious to Anthony and by offensively abusing them.

This method of ‘mental teasing’ also occurs in other Bosch paintings depicting saints. De Bruyn then gives five examples of ‘mental temptations’ in the Lisbon triptych, each time referring to texts about St Anthony that were accessible to well-educated persons in the late Middle Ages and that may have inspired the painter. This concerns the following scenes: the army on its way to a village (centre panel), the devils who have prepared a table with food and drink (lower right interior panel), the three devils reading (or singing) from an open book (centre panel), the weird-looking bathhouse/brothel with naked swimmers (centre panel) and the devilish pelgrims on their way to a brothel (left interior panel).

In some of the Lisbon triptych’s secondary scenes it is not Anthony but Jesus who is the major victim of the devil’s parodies. Examples of this are the monstrous bird devouring its own young (lower left interior panel), the group around the giant rat (centre panel) and the mannikin dressed as a child and using a walking frame (right interior panel). That the devils are poking fun at Jesus in order to hurt Anthony’s feelings should come as no surprise: Athanasius’s Greek vita mentions Jesus at least fourty times (in a positive way, obviously).

[explicit 8 May 2017]