Fischer 2016

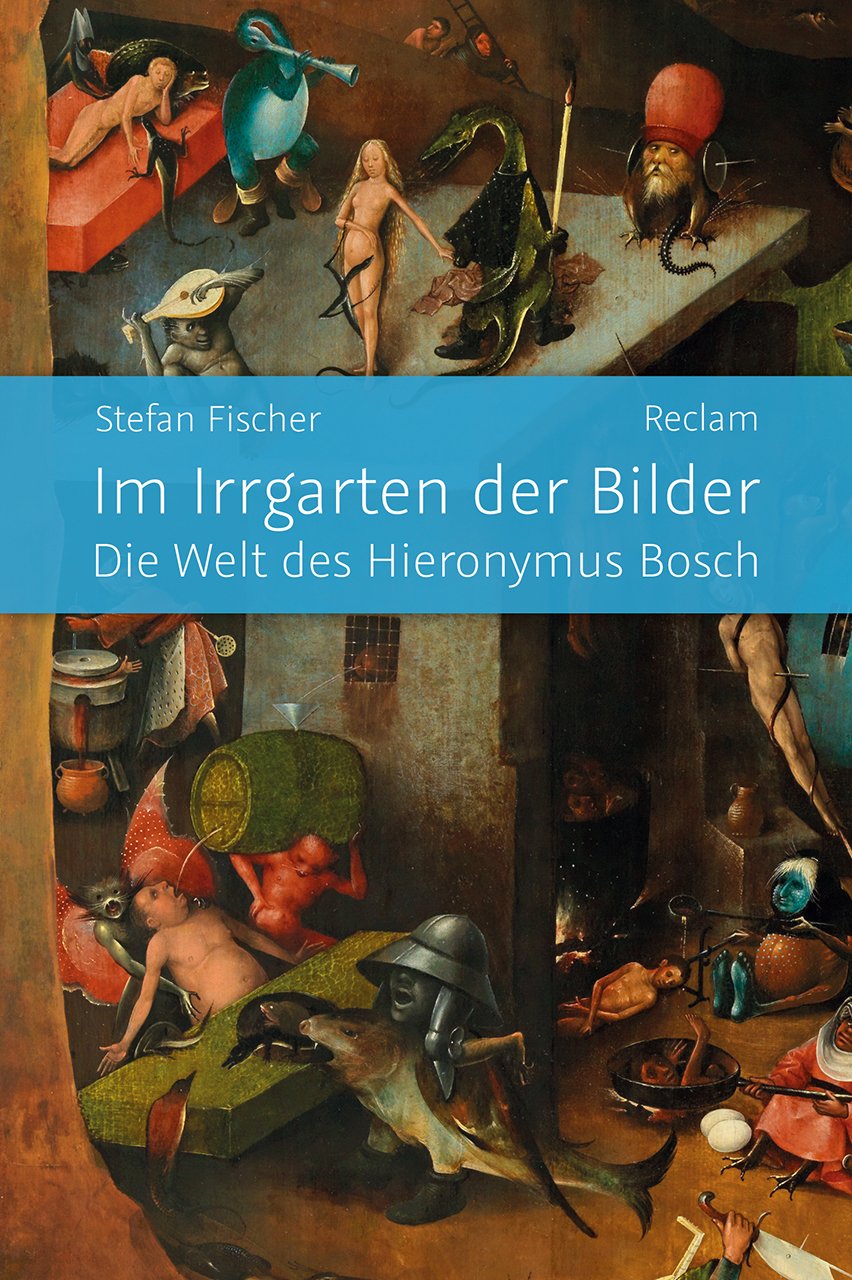

Im Irrgarten der Bilder – Die Welt des Hieronymus Bosch (Stefan Fischer) 2016

[Reclam, Stuttgart, 2016, 237 pages]

This very sound Bosch monograph addresses the general reader and comprises thirteen chapters.

Der Fürst und der Maler [pp. 7-13]

This chapter focuses on Bosch’s cultural-historical context. The highest nobility in the Netherlands (Maximilian I, Philip the Fair) was responsible for some major commissions, and yet Bosch’s art was produced far away from the centres of nobility, namely in ’s-Hertogenbosch. At the end of the fifteenth century, though, this city went through an economic and cultural growing process. ’s-Hertogenbosch had closer ties with the East than with the South. Clergy was strongly present in ’s-Hertogenbosch. Of major importance were the Modern Devotion (with its admiration for early Christian ascetics such as St Anthony and St Hieronymus), the Dominicans, the Brethren of the Common Life, and the Latin school. Typical of the urban early Humanism in ’s-Hertogenbosch were the interest in parody and comical satire, and also a predilection for monstrous, hybrid, grotesque, and fantastic motifs, which could function as allegorical references to the works of the devil and to the consequences of sin.

Jeroen van Aken – Spross einer Malerdynastie [pp. 14-32]

First an overview of the biographical data regarding Bosch and his family. The Brussels Crucifixion and the Ghent St Hieronymus are considered Bosch’s oldest paintings that have come down to us. According to Fischer, the patron represented in the Crucifixion is an executioner. Striking – in the paragraphs dedicated to Bosch’s presumed Latin education – is the attention (inspired by Paul Vandenbroeck’s research) paid to the Latin treatise De disciplina scholarium, which is the source for the Latin line in the The field has eyes drawing.

Eine keineswegs geheime Bruderschaft [pp. 33-47]

Bosch probably attended the Latin school in ’s-Hertogenbosch and joined the local Brotherhood of Our Lady in 1486/87. In 1488/89, he already joined the inner circle of ‘sworn brothers’ of this elite society, which means that Bosch was a cleric and had received one of the minor orders. The Brotherhood’s contacts with the local Dominicans were good. Considering this social context, it is absurd to claim that Bosch would have painted for a heretical sect. The architect Jan Heyns was also a member of the Brotherhood. Bosch’s St John on Patmos (Berlin) and St John the Baptist (Madrid) were painted for the altarpiece of the Brotherhood’s chapel in the Church of St John (Fischer presents this as a proven fact, whereas it is a hypothesis). The apostle St John and St John the Baptist were the patron saints of the Church of St John and of the Brotherhood. The strange plant in the St John the Baptist panel hides a male patron. Stylistic analysis leads to the conclusion that it was Bosch himself who overpainted the patron. The motif of a devil stealing St John’s inkpot in the Berlin St John on Patmos can also be seen elsewhere and is borrowed from the legend of a local saint who was also called Johannes (John). No further information about this is given. The little devil in Berlin clearly makes a comical impression. The Berlin panel probably shows Bosch’s oldest signature that has come down to us. Of course, the name ‘Bosch’ refers to ’s-Hertogenbosch. In their engravings, Alart du Hameel and the ‘Master Bosch with the knife’ also referred to the city where their art was produced. The Brotherhood showed a lot of interest in national and international contacts.

Reformatio! [pp. 48-67]

The life and the Passion of Christ and the Imitation of Christ idea are major themes in the art of Bosch. This chapter focuses on six paintings. The Frankfurt Ecce Homo was probably commissioned by patrons from or near ’s-Hertogenbosch. The typological details, the Antichrist figure, and the patrons in the Prado Adoration of the Magi are discussed. According to Fischer, the black king and his helper carry negative attributes referring to unchastity, the dancers in the left interior panel are part of a landscape which is represented as pagan and dangerous, and the animals in the right interior panel are bears attacking humans. Then follow the Boston Ecce Homo triptych (a workshop product), the large and the small Carrying of the Cross (Madrid / Vienna), and the London Crowning with Thorns. The child on the reverse of the Vienna Carrying of the Cross panel is the Christ Child. Bosch’s representation of the Passion agrees with the reformatio idea that was on the rise around 1500: the ritual character of religion was replaced more and more by a reformation of the individual and of society, with a focus on a practical way of life bound by religious standards and moral correctness.

Der Wald hat Ohren, das Feld hat Augen [pp. 68-80]

Eight drawings by Bosch have come down to us. Fischer discusses the Rotterdam Owls’ Nest and the Berlin The field has eyes. He points out that in this latter drawing the fox underneath the tree has killed (erlegt) a rooster. Fox and owl refer to evil, of which the represented proverb warns. Also the birds in the owl’s neighbourhood are seen as referring to sin and evil. An elaboration on the owl points out the poly-interpretability of symbols in the Middle Ages. In most cases, the owl was a negative symbol, but it could also refer to Christ. Bosch’s oeuvre has a moral component (probably inspired by his school training and by early Humanism), but this is not the major goal, it supports a religious message aimed at the End of Times.

The Rotterdam St Christopher (according to Fischer shortened at the top) was also inspired by early Humanism and announces the Reformation. Christopher is no longer represented as a patron saint (as in popular superstition), but as an example for the pious Christian. The weird tree is said to allude to gluttony, a sin committed by Christopher according to his legend. The three small figures to the right (underneath, in, and atop the tree) are three hermits, and Fischer relates this number to the use of the number three in mystical literature from the Low Countries (Modern Devotion, Ruusbroec, Brugman).

Schöpferische Kraft und Bilderlabyrinthe [pp. 80-91]

This chapter is more theoretical and deals with Bosch’s method and style. The art of Bosch is based on the combination of familiar things, resulting in the creation of something new. Bosch made use of rhetorical stylistic devices such as accumulatio, exemplum, parallellism, opposition, alienation, and neology. According to Fischer, this was a result of Bosch’s Latin school training. Bosch’s devils are grotesque hybrids: from a moralistic point of view, they are the opposite of Christ and of the divine world order. Two drawings with monsters and the Vienna Treeman drawing are discussed in this context. Bosch also used the varying registers which we know from literary texts (high, medium, low). The low register often functions as a parody of the high register, which explains why Bosch’s devils and droleries also have a humoristic aspect. Bosch’s painting and drawing technique was also innovative because he worked in a swift and direct way. In this context, Fischer discusses the two Berlin drawings with The Battle between the Birds and the Mammals that have recently been added to the Bosch catalogue. These drawings show that Bosch’s iconographical repertoire also comprised profane elements.

Das Schmunzeln des Antonius [pp. 92-106]

This chapter deals with the Lisbon St Anthony triptych. The triptych reveals a sound knowledge of St Anthony’s life, based on the Vitas Patrum texts. According to Fischer, Bosch may have read such a text himself, copies of it were available in ’s-Hertogenbosch with the Brothers of the Common Life and in the monastery of the Wilhelmites. Fischer points out several passages from Anthony’s vita that may have inspired details in the triptych. Bosch’s triptych, often imitated in the sixteenth century, offers a new interpretation of the St Anthony theme. Fischer relates the painting to grotesque-absurd literary texts (Mürner, Rabelais, Folengo).

Im (Irr-)Garten der Lüste [pp. 107-128]

A complete chapter is dedicated to the Garden of Delights as well. This triptych is said to have been painted around 1503 and to have been commissioned by Engelbrecht II of Nassau on the occasion of the marriage of his cousin Henry III of Nassau (p. 124). Just as the St Anthony triptych, this painting aims at ‘learning and educating’. The centre panel represents Mankind before the Flood. The black people are the offspring of Cain. The Sicut erat in diebus Noe theme was inspired by the Gospel of Matthew (24, 37-39). The figures and objects in the right interior panel (Hell) refer to Bosch’s own times.

Die Rückkehr der Habsburger oder das Weltgericht [pp. 129-146]

Fisher focuses on the Vienna Last Judgement triptych. This is perhaps the triptych which was commissioned by Philip the Fair in 1504. The saints in the exterior panels, St James and St Bavo, refer to Spain and Flanders. The patron in the lower left corner of the centre panel, only visible in the underdrawing, may be Charles the Bold. In this painting, Bosch’s devils often have a comical effect. To make this more plausible, two letters written by Philip II are quoted. The end of this chapter pays quite some attenttion to Alart Du Hameel.

Höllen und Eremiten für den Markt [pp. 147-160]

This chapter deals with the Bosch paintings that have been located in Venice for ages: the St Ontcommer triptych, the Hermits triptych, and the wings with Paradise and Hell scenes. Perhaps these paintings reached Italy through the international art market. Bosch’s cousin Jan (a son of Bosch’s brother Goessen) was married to a bastard daughter of Lodewijk Beys, one of Bosch’s neighbours who travelled as a pilgrim to Jerusalem several times: this Beys could be the link between Bosch and Venice. Perhaps the Antwerp art market also played a role. After 1500, when his fame had spread abroad, Bosch was more and more in need of assistants. That is why Fischer now focuses on Bosch’s workshop. The only family member that could have been a workshop assistant is Bosch’s cousin Anthonis van Aken, the youngest son of Bosch’s brother Goessen. Goessen’s eldest son Jan was a sculptor. The Bruges Job triptych is a product of Bosch’s workshop. The escutcheons in the exterior panels allow for a link between ’s-Hertogenbosch and Antwerp.

Die Erfindung der Genre-Malerei [pp. 161-184]

Bosch was not a fanatical moralist or pessimist and did not only paint devils and hells. Another component of his art is genre painting, with depictions of daily life representing moral ideas and the teachings of the Church and often revealing a comical note. Probably, this tendency in the art of Bosch is related to the growing Humanist character of the intellectual elite in the Low Countries and in Germany after 1500, also in ’s-Hertogenbosch. Paintings such as The Cutting of the Stone and The Juggler are dominated by the principle of negative self-defining: the viewer is confronted with examples of improper behaviour. Fischer uses the German phrase Negativ-Exempla for this. But with Bosch, the genre-like details keep functioning within an eschatological frame, for example in the Seven Deadly Sins panel (Madrid).

In this context, the reconstructed Pedlar triptych is discussed as well. The triptych shape is pivotal in the art of Bosch, and although Bosch’s triptychs have a religious character, it would be unhistorical to see them as altarpieces by definition. According to Fischer, the (lost) centre panel of the Pedlar triptych probably showed The Wedding at Cana (copies: Rotterdam and a drawing in the Louvre). The pedlar figure in the exterior panels of this triptych (and of the Haywain triptych) is a repentful sinner and symbolises man as a pilgrim of life. In the Rotterdam tondo the pedlar walks toward a red cow that stands for Christ. The aggressive dog is an image of the devil. It is useless to call Bosch’s triptychs profane paintings: even though they were not necessarily sacral cult objects, they still had a religious function.

>>Des Menschen Tage sind wie Grass<< [pp. 185-202]

The Haywain, ‘one of Bosch’s latest works’, confirms the success of Bosch’s innovative pictorial themes with the high nobility. The Christ figure in the upper part of the centre panel shows His wounds, He is both the Man of Sorrows and the Judge of the World. The Escorial Haywain is a copy dating from around 1550. In this chapter, Fischer also discusses the Rotterdam Flood panels. The tondos in the exterior panels probably represent The Temptation and Salvation of Job. Attention is also paid to Bosch’s use of colours. At the end of his life, Bosch’s rich use of colours and the grotesque character of his art diminished (fewer monsters and devils). Bosch’s spiritual message is not based on pessimism but on the desire to show the viewers of his panels the right path to the Hereafter. Bosch died in 1516, possibly due to an epidemic of pleuritis.

Kunst im Namen Boschs [pp. 202-224]

This chapter deals with the imitation and the afterlife of Bosch’s art. The ‘copy, imitation, or forgery’ issue causes a lot of problems. The Bruges Last Judgement triptych is the work of a talented workshop assistant, perhaps the famous discipulo mentioned by Felipe de Guevara. The imitations of Bosch multiplied as soon as his works were also accessible to painters who were not workshop assistants. In the majority of cases, these imitations represent hell scenes and grotesque monsters. Antwerp in particular yielded numerous Bosch followers: Jan Wellens de Cock, Hieronymus Cock, Peter Huys, Jan Mandijn, Peter Bruegel the Elder. Fischer wonders whether the Bruegel family had access to study sheets by Bosch. Philip II and Rudolf II were renowned collectors of the art of Bosch. In Mechelen (Malinois), the Verbeeck family worked in the wake of Bosch. Because of the moral and didactic message and using aesthetic-parodical means, Bosch plays the role of the devil in his paintings, which allowed him to paint delicate things, whereas it is in fact the devil who ‘generates’ the diableries. This can be compared to the role of the fool adopted by Erasmus in his Praise of Folly. Bosch painted moralising, satirical, and grotesque works. Early Spanish authors such as Felipe de Guevara and José de Siguënza were convinced that Bosch’s grotesque creations and monsters served a religious purpose.

Some things that I agree with

Some things that I do not agree with

[explicit 7th June 2019]