Higgs Strickland 2016

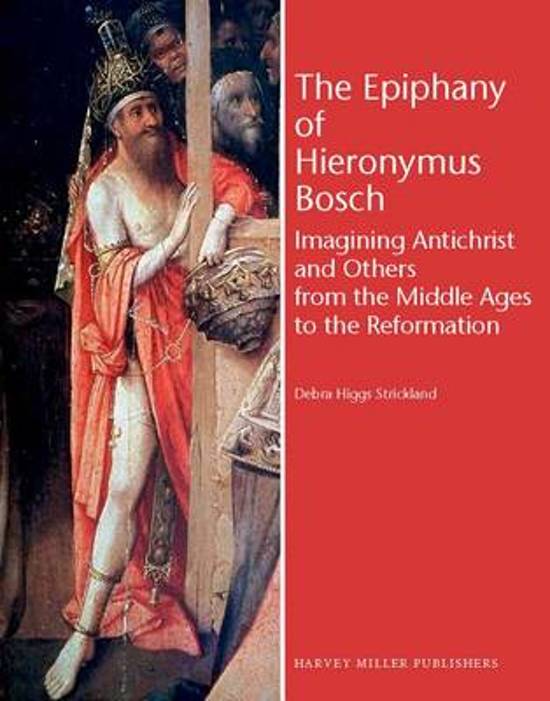

The Epiphany of Hieronymus Bosch – Imagining Antichrist and Others from the Middle Ages to the Reformation (Debra Higgs Strickland) 2016

[Harvey Miller Publishers-Brepols Publishers, London-Turnhout, 2016, 301 pages]

Introduction – Hieronymus Bosch and the Prado Epiphany: Time and Painting [pp. 6-21]

In this monograph, dealing with Bosch’s Adoration of the Magi triptych (Madrid, Prado), Higgs Strickland is not primarily interested in Bosch’s original intentions with this triptych, because we are unable to read Bosch’s mind, and we know little or nothing about the painting’s patrons and original function. In the past, the cultural-historical approach to Bosch, the approach that attempts to link a work of art as much as possible to its original historical context, has only yielded diverging interpretations. Higgs Strickland wishes to avoid this by sticking to a receptional-historical approach: ‘Rather than expending time and energy on mind-reading Bosch, I focus on the reception of his work in light of changing cultural interests with which we are on solid historical and documentary ground’ [p. 16]. In other words: in this book the author wants to study in what ways Bosch’s triptych was looked at and interpreted by consecutive generations of viewers, limiting herself to the period that runs from Bosch’s own time to the early Reformation. But she adds: ‘Of course, this approach has serious limits, mainly that the codes of looking I construct in the next few chapters can only produce a hypothetical – as opposed to a “proven” – set of possible viewer responses. On the other hand, in the absence of records telling us something specific about viewer reactions, this might be the best we can do’ [p. 16].

The words ‘solid’ and ‘hypothetical’ were underlined by me… Regarding the contradictory results of the cultural-historical approach to Bosch, Higgs Strickland makes the logical error that can also be found elsewhere: when interpretations of a work of art contradict each other, this does not automatically mean that all these interpretations are wrong.

Chapter 1 : First Encounters [pp. 22-69]

This chapter investigates what ‘preceded’ the Prado Epiphany: what did medieval Christians think about the Adoration of the Magi theme, and what did the literary and iconographical traditions look like? The objective is to get a better idea of what is ‘unusual’ about Bosch’s Prado Epiphany. The Bible story about the Three Magi (Matthew 2, 1-12) is said to touch upon three motifs: enmity, the part played by the Jews, and time. These motifs will be dealt with in the next chapters. First, the Three Magi theme in medieval literature and iconography is studied. Attention is paid to the following topics: the word ‘magus’, the number of Magi, the ages and the names of the Three Magi, their attire, the fact that they are kings, their gifts, their headwear, their skin colour, the star, the liturgy dealing with the Epiphany, and theatre plays dealing with the Three Magi. Furthermore, the anti-Jewish aspects of the Three Magi theme, the ox and the donkey, the relics of the Three Magi in Cologne, John of Hildesheim’s Historia Trium Regum, the function of the theme within the struggle between the pope and the German emperor and within urban self-promotion (Cologne), and the armies of the Three Magi.

Except for the ox, Bosch represented all the theme’s traditional elements: the Three Magi and their gifts, the Christ Child and Mary, Joseph, the stable, the shepherds, the donkey, the armies of the Three Magi, the star, Jerusalem, two patrons and the parallel with the Incarnation during Holy Mass (see the exterior panels). But Bosch’s Epiphany also has a number of unusual aspects: the three armies that are represented at a distance from the Three Magi, the dancers and the aggressive animals in the wings, the statue of an idol in the far distance, the weird city in the background, the isolated figure of Joseph, the voyeuristic shepherds without sheep, and of course the remarkable pale figure inside the stable. Furthermore, the Three Magi’s gifts and clothes allude to evil: the toads, the monsters on the robes of the black king and of his servant. Bosch’s painting is ‘more ominous than joyful’ and makes the viewer look for deeper ideas and messages. In this respect, the pale figure (the ‘fourth king’) in the stable is pivotal.

That this pale figure is holding the crown of the middle king (p. 62, mentioned again on pp. 97 and 209) does not seem correct: the pale figure is holding his own crown… (on this issue, see Cat. ’s-Hertogenbosch 2018: 50).

Chapter 2 : The Magi Across Time [pp. 70-111]

This chapter focuses on the eschatological elements of the interior panels, in other words on the references to the End of Days. The so-called ‘fourth king’ is interpreted as the Antichrist, one of the reasons for this being the fake crown of thorns that is worn by this figure. The author surveys the traditional ideas about and representations of Antichrist in medieval texts, images, and popular stories. The Antichrist legend has a strong anti-Jewish aspect, and the author argues that echoes of this can be detected in the figures in the stable, the donkey, the owl, and the shepherds: all these details are negative references to the Jews. The dilapidated stable itself refers to the Ancient Law. In the Antichrist legend a role is played by three kings (the kings of Egypt, Libya, and Ehtiopia). They were misled by Antichrist and can thus be considered negative counterparts of the biblical Three Kings. But Bosch’s Three Kings are also said to be suspect, and so they too refer to the End of Days. According to Higgs Strickland, especially the black king and his servant are marked with negative connotations. In spite of the fact that black figures could also be seen as positive in the Middle Ages (Priest John, black saints such as St Maurice), negative meanings associating them with sin, inferiority, and the devil, were of major importance. That is why the author interprets Bosch’s black king as the Ethiopian king worshipping Antichrist, because of a number of details ‘that disrupt a positive reading of his nature and motivations’ (p. 92). Apart from the black skin colour, such details are the monsters on the robes of the black king and his servant, and the fact that they are wearing earrings (the right thigh of the ‘Antichrist’ figure is also pierced by a ring). Even Bosch’s two other kings and their gifts are discredited: the kneeling eldest king, for example, is wearing a red robe just like the ‘Antichrist’ figure, and the crown of the middle king is said to be held by ‘Antichrist’.

Higgs Strickland is taking things to great (probably too great) lengths by suggesting on page 97 that Bosch put his signature in golden letters right underneath the black king in order to refer to his ‘own self-perceived sinful state’ – admittedly followed by a question mark. According to the legends, Antichrist will use gold to bribe people. It was already signalled above that the ‘Antichrist’ figure is nót holding the crown of the central king. Having arrived at this point of the monograph, one has the strong impression that Higgs Strickland is more than once guilty of Hineininterpretierung.

The author then searches for other details that may refer to the End of Days. In the central panel, these are the city of Jerusalem (where the Antichrist will have the Temple of Solomon rebuilt), the statue of an idol near the city, and the armies of the Three Magi (according to the legends pagan armies led by the Antichrist will appear from the East, South, and North). Higgs Strickland is less sure about the dancers in the left interior panel and the attacking wolves in the right interior panel. The dancers may refer to the unwarranted joy of Antichrist’s followers after his defeat, and although she cannot link the attacking wolves to the ‘Signs of Doom’, the signs that will precede the coming of the Antichrist, this detail may refer to the chaos at the End of Days. In the left interior panel the isolated Joseph figure, who is ‘perhaps’ drying the Christ Child’s diapers, probably refers to the redundancy of Judaism in the new Christian era (because of the surroundings in which he is placed) and (because of his direct gaze at the viewer) to the fact that Christ’s arrival on earth did not change the sinful course of humanity, which will lead to the coming of the Antichrist. St Peter and St Agnes function as witnesses to Christ’s divinity, and the two patrons probably represent every Christian man and woman with their free will to choose Christ or Antichrist.

Higgs Strickland concludes that Bosch painted a deeply pessimistic typology of the coming of Christ as a prefiguration of the coming of Antichrist. ‘My eschatological interpretation of the interior panels of the Prado Epiphany is grounded in early modern beliefs about Antichrist, Jews, and the end of time, inherited from late medieval tradition and widely disseminated across literary and visual cultures’ (p. 103).

Chapter 3 : In Bosch’s Day: Modern Devotion, Disease, and Salvation [pp. 112-149]

‘With this chapter, I begin my speculative account of the reception of the Prado Epiphany by its different generations of viewers, beginning with its first one’ (p. 113). The italics of the word ‘speculative’ are mine. The main question here is: how did Bosch’s contemporaries view the Prado Epiphany? In spite of the fact that Bosch’s being influenced by the Modern Devotion is hard to demonstrate, the author still examines this possible influence because the Modern Devotion was strongly present in Bosch’s immediate surroundings. Common to both Bosch’s Epiphany and the ideas of the Modern Devotion is the focus on Christ and on the poverty of the new-born Christ Child. There is also the pessimistic view on the state of the Church and of the world (contemptus mundi). If we interpret the large Mary figure as referring to the Church (Ecclesia), the dilapidated stable can be viewed as a comment on the corrupted state of the Church (whereas in the preceding chapter this same stable was interpreted as a reference to the redundancy of the Jewish Old Law…). The sinister skyline of the city in the background suggests that this could be the Holy City in the guise of the unholy Babylon. The dilapidated stable, the dancers, the lamb among wolves in the left and right interior panels: all of these details may refer to the corruption of the Church.

In Bosch’s Epiphany the themes of eschatology and corruption are linked to the physical signs of disease. The pale skin of the ‘fourth king’ may suggest leprosy, the wound on his leg may suggest syphilis. In the Middle Ages, leprosy and syphilis could be associated with the Jews and with sin. This agrees with the ideas of the Modern Devotes, who viewed the Jews as enemies of Christ. By pairing Christ’s birth with a Mass of St Gregory (see the exterior panels) Bosch linked Christ’s incarnation on earth to his perpetual (re)incarnation via the mystery of transsubstantiation during Holy Mass. The Modern Devotes worshipped St Gregory in a special way, and they also viewed the celebration of Mass as a means of spiritual growth. Furthermore, they propagated pious and empathising meditation on the Passion (see the Passion scenes above the altar). And yet, in the end Higgs Strickland argues that Bosch’s exterior panels were not suitable for this form of meditation, because the Passion scenes (in particular those at the top) are too ‘illusionistic’. The viewer might confuse the representation with what is represented (something from the real world), a danger that was warned of by Geert Grote.

The author concludes: ‘Although it is possible to identify these points of correspondence between Bosch’s iconography and some of the main spiritual goals detailed in the literature studied and championed by the Brethren, further claims that Bosch was directly influenced by the movements’s goals or that the Prado Epiphany addressed or satisfied its specific spiritual requirements are in my opinion untenable. (…) I would even go so far as to suggest that the Prado Epiphany is the antithesis of a good and useful image from the perspective of the Modern Devotion’ (pp. 141-142). The dilapidated state of the buildings, the aggressive background scenes and the pale figure in the stable, in short the omnipresent pessimism do not agree with the uncomplicated contemplation of the biblical event that was typical of the Modern Devotion.

After all this, the reader cannot refrain from asking: if Bosch’s triptych was not influenced by the Modern Devotion, why then spend a complete chapter on it? Again and inevitably, the feeling is growing that Higgs Strickland is not a reliable guide in Bosch country, in spite of the fact that she seems to have done elaborate academic field work, at least concerning issues that are not (directly) related to Bosch.

Chapter 4 : Beyond Time: The Mass of St Gregory (pp. 150-193)

This chapter examines how Bosch’s contemporaries (the first generation of viewers) interpreted the Mass of St Gregory in the exterior panels. Bosch paired a Mass of St Gregory with an Epiphany in order to generate new, deeper meanings, whose retrieval requires close scrutiny of iconographical details on the part of the viewer. With the combination Mass of St Gregory / Epiphany Bosch departs from convention, but also the Passion scenes seem to be a unique contribution to Gregorymass iconography. Like the interior panels, the exterior panels simultaneously evoke the present (the two patrons, the ever-repeated miracle of the transsubstantiation during Mass), the past (the miracle of the Gregorymass, the Passion of the Christ), and the future (the End of Days, when according to some sources Christ will appear again as the Man of Sorrows surrounded by the Arma Christi). Again, strong focus is placed on the negative role of the Jews by means of the Passion scenes (here substituting the traditional Arma Christi in other Gregorymass representations). Higgs Strickland mentions Lynn Jacobs’ observation: when the triptych is opened, the Christ figure above the altar and the crucified Christ are split up, and this refers to the breaking of the Host during Mass. According to Higgs Strickland, the fact that Christ is ‘split up’ twice agrees with the fact that during consecration the Host is broken twice (resulting in three pieces). Regarding the link between exterior and interior panels: the exterior panels with the celebration of Mass and the imitation of Christ idea offer a positive alternative for the sinfulness dominating the interior panels (even ‘including the magi’, p. 188).

Quite a number of the interpretations offered in this chapter are clearly far-fetched and do not convince the reader. A good and typical example of this can be found on page 187: even the fact that the two Christ figures in the exterior panels are split up when the triptych is opened, is said to refer to the conflict and division within the corrupted Church. ‘The viewer can also see the split images of Christ in the Gregorymass as symbolic of conflict and division within the corpus Christi mysticum, identified with the Christian Church.’ One has to admit: it cannot get much crazier, when even a Christ figure is said to have negative connotations.

Chapter 5 : The Next Generation, the Pope, and the Turks (pp. 194-261)

Chapter 5 examines how the ‘second generation’ of viewers (the generation after Bosch’s death in 1516) might have approached Bosch’s Epiphany. The author’s approach remains speculative: ‘I have grounded my speculative approach to the painting’s reception by the generation after Bosch in a selected set of contemporary ideas that provide changed interpretative contexts for the work’s key iconographical elements’ (p. 195). At first, the focus is on the ideas of Protestantism, in particular of Luther, by which the pope is constantly viewed as the Antichrist. Bosch’s Antichrist figure in the stable, whose headgear can be considered a parody on the papal tiara, could be interpreted as a reference to the pope by Protestants. In the eyes of Protestants the Gregorymass in the exterior panels could refer to everything that was wrong within the Catholic Church. The stable, which is ‘threatened’ by shepherds, could be related to Christ’s sheepfold invaded by unworthy (Catholic) clerics, and the wolves in the right interior panel could be viewed as the Catholic wolves threatening the Protestant sheep: two topical ideas of the Protestant, anti-Catholic propaganda. The star in the central panel could refer to the danger of syphilis (compare the sore on the leg of the pale figure), to the Turkish menace (see the three armies in the background), and to the fall of the papacy.

The Protestants (i.a. Luther) and the Humanists (i.a. Erasmus) had a very low opinion of the Turks. They were viewed as a threat to Christianity and as a divine punishment of Christian sinners. They also associated the papacy with the Turks. For Protestant viewers, the three armies in Bosch’s central panel could evoke similar associations, whereas they might interpret the pale figure in the stable as the Antichrist, as a Turkish sultan, or as the pope conspiring with the Turks. Actually, the negative opinion about the Turks had already caught on during Bosch’s lifetime (after the fall of Constantinople in 1453). ‘Such was – and is – the complex contingency of Bosch’s painted forms’ (p. 227).

In this chapter, speculation is raised one level higher, and the reader has the impression that the iconographical truth of Bosch’s Epiphany is stretched more and more. All the time, the author tries to reconstruct how sixteenth-century Protestants might have viewed Bosch’s triptych. But on page 196 Higgs Strickland herself points out: ‘Luther condemned the cult of the magi, which he claimed was created to make money; he said that the whole story was a lie and that the relics in Cologne were fake’. This raises the following question: would sixteenth-century Protestants have shown much interest in Bosch’s triptych with its focus on four saints (the Three Magi and St Gregory)? Is it not far more logical that a sixteenth-century Protestant could not care less about an Epiphany painting?

Chapter 6 : The Next Generation and the Jews [pp. 236-261]

The sixth chapter tries to find out how the pale figure in the stable and other details of Bosch’s triptych could be associated with the hated Jews by sixteenth-century Catholics, Protestants, and Humanists. The Jews were often accused of Host desecration and of ritual murders. That is why sixteenth-century people could associate the Christ Child in Bosch’s central panel with the Host, Mary with Ecclesia, and the pale figure with Jews who try to kill Christ again through the desecration of Hosts. According to the author, this association is endorsed by the exterior panels, which reminded sixteenth-century people of what the stabbing, burning, or breaking of a Host meant: the renewed crucifying of Christ. The pale figure in the stable, ‘a dangerous Jewish predator’, and the Passion scenes and the Man of Sorrows (whose surrogates the young Christians were) in the exterior panels could remind a sixteenth-century viewer of the ritual murdering of Christian boys by Jews. The ‘crown of thorns’ of the pale figure is a visual metaphor for the unfeeling desecrators of Christ, the livng Host (the pale figure does not feel the crown of thors, for it is worn on top of a headgear).

Furthermore, the Jews were accused of having caused the plague by poisoning sources. If we interpret the pale figure as Herod, this could signal that the Jewish conspiracy had already begun when Jesus was born. And there is also the legend of the Red Jews: Jews who had been locked up inside a mountain by Alexander the Great, and who would appear again together with the Black Jews under the rulership of the Antichrist at the End of Days. In the eyes of a sixteenth-century person who knew this legend, the armies in the background of the central panel could refer to this. According to late medieval tradition, these Red Jews would have red hair and red beards (p. 253). That is probably why the author does not mention the pale figure in the stable in this context, in spite of his red, sunburnt face, for he clearly does not have red hair or a red beard. Luther and Erasmus claimed that unworthy Christians were as bad as Jews. That is why the anti-Jewish elements of Bosch’s triptych could also be seen as a warning directed at Christians, admonishing them not to sin and thus to avoid re-crucifying Christ over and over again.

Epilogue : Other Paths, Future Stories [pp. 262-273]

Looking back, the author notes: ‘Inside, the pale figure, with his multiple identities, remains the chief surveyor of the scene’s multiple temporalities as a constant signifier of enmity and contingency. This is why all of my different readings of the Prado triptych begin and end with this figure. I hope to have persuaded the reader that over time, the many meanings inscribed in the Prado Epiphany had the capacity to serve different spiritual, devotional, and political interests’ (p. 264). The Epilogue pays some attention to the sixteenth-century copies of the Prado Epiphany. The copies in Upton House, Petworth House, and Philadelphia simplify and ‘conventionalize’ what Bosch painted, numerous enigmatic details are changed or left away (except for the pale figure in the stable), and thus the copyists drastically eliminated the original’s eschatological dimension and contingency.

In a certain way, this could be considered an argument against Higgs Strickland’s far-reaching hypothetical reconstructions. These deal with the potential ways in which potential viewers might have looked at Bosch’s triptych, based on the reconstruction of a potential frame of mind. But in the case of the copies we are dealing with highly manifest and not just ‘potential’ receptions of Bosch’s original by sixteenth-century persons, and what is the result? Nothing of Higgs Strickland’s elaborately reconstructed eschatological dimension of Bosch’s triptych remains, except for the pale figure in the stable…

‘It is with post-Boschian meanings that this study has been largely concerned as a demonstration of the potentially long and active role played by great works of art over time’ (p. 272). But one has the strong impression that the author is exaggerating when she is continuously pointing out details referring to negativity, sinfulness, and threat. A nice example of this on page 264, where she is writing about the ‘discordant details’ and the ‘ominous mood’ of the Epiphany triptych by a follower of Bosch in the Erasmushuis museum (Anderlecht): even the angel in the left interior panel who is helping Joseph with the drying of the Christ Child’s diapers is interpreted as a detail referring to ‘disquiet’.

OVERALL ASSESSMENT

In 2018, Matthijs Ilsink, Jos Koldeweij, and Ron Spronk published From Bosch’s Stable – Hieronymus Bosch and the Adoration of the Magi, a catalogue accompanying the exhibition of the same name in the ’s-Hertogenbosch Noordbrabants Museum (1st December 2018 – 10th March 2019) and focusing on Bosch’s Prado Epiphany triptych and its copies. It is remarkable that Higgs Strickland’s book about the same triptych, which was published two years earlier, is mentioned in the bibliography, but is only granted three short references in the text itself, and even then only in footnotes (footnotes 28, 57, and 68), with no special attention whatsoever to Higgs Strickland’s approach. Only footnote 57 briefly points out (regarding the interpretation of the pale figure in the stable): ‘The recent detailed monograph on this painting by Debra Higgs Strickland, published in 2016, is also indebted to Brand Philip’ (see Brand Philip 1953). Does this imply that Ilsink, Koldeweij, and Spronk were not very enthusiastic about Higgs Strickland’s interpretations?

In a mild, but also rather superficial review, published online, Al Acres raises the question: ‘Is it possible to see too much in a single work of art?’ Acres himself answers this question reservedly: ‘Readers will resist some of the specific associations she proposes, but will find it difficult to dismiss their viability for many sixteenth-century minds’. But the question is definitely relevant, in view of Higgs Strickland’s focus on the contingency of Bosch’s oeuvre, a term that is apparently indebted to the Bosch approach of Joseph Leo Koerner (who is mentioned several times throughout the book, and always with approval). On page 216 the same phenomenon is referred to by means of the term amphibolism (borrowed from Luther’s opinion about the prophecies of Johannes Lichtenberger). The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English (1972 edition) defines the adjective contingent as follows: ‘uncertain, accidental, dependent on something thay may or may not happen’. So, Bosch’s contingency or amphibolism means that what Bosch painted, can be interpreted in different ways.

This idea is not completely new. Already in the 1970ies there was a trend in the literature on Bosch that could be described by the term ‘poly-interpretability’ (in German: Mehrdeutigkeit). In 1975, for example, John Rowlands wrote (I quote the German translation): ‘Wir sollten, so meine ich, immer mit unseren Annahmen vorsichtig sein, wenn wir auf eine plausibele Erklärung für irgendein Detail von Bosch gestossen sind. Es muss nicht die einzige sein, die der Maler beabsichtigt haben könnte. Ein so reich begabter Künstler würde kaum in einer so engen und eingeschränkten Art gearbeitet haben’ (in my opinion, we should always be cautious with our presumptions, when we have found a plausible explanation for some detail in the art of Bosch. It does not have to be the only one that the painter had in mind. An artist of such rich talent will not have worked in such a narrow and limited way) [Rowlands 1975: 7]. And in the same year, Hans Holländer wrote about the Garden of Delights (I quote the Dutch translation): ‘Tot nu toe staat vast dat een bevredigende interpretatie van dit schilderij niet bestaat. We kunnen slechts voorspellen dat iedere poging tot een interpretatie die maar voor één uitleg vatbaar is, zal mislukken. We zijn gedwongen tussen verscheidene standpunten heen en weer te springen’ (for now, it is certain that a satisfactory explanation of this painting does not exist. We can only predict that every attempt to interpret it in a one-sided way will be doomed to fail. We have to maneuver to and fro between different points of view) [Holländer 1975: 167]. On page 245 of Higgs Strickland’s monograph we read: ‘Like many of Bosch’s eccentric motifs, this one can be interpreted in different ways, because, as I have maintained throughout this study, interpretative choices are multiple and must be made by the viewer, with or without secure knowledge of what the artist may or may not have intended’. There is an important difference, though, between Higgs Strickland’s approach and the ‘poly-interpretability’ of the 1970ies: authors such as Rowlands and Holländer believed that Bosch intentionally filled his paintings with ambiguous or even multi-meaningful details, whereas Higgs Strickland explicitly claims not to be interested in Bosch’s intentions, because she is not able to read his mind. What her monograph tries to do, is to reconstruct different potential reactions of different potential viewers to Bosch’s Epiphany triptych.

Not many among those who are familiar with the art of Bosch will want to deny that this painter often confronts us with enigmas, mostly regarding details and sometimes regarding a complete panel (see, for example, the central panel of the Garden of Delights). That different authors come up with different interpretations, or that one author argues that it could be this, but also that, and even such and such as well, is not unlogical. But here, the big danger lurking around the corner is obviously Hineininterpretierung, when explanation is pushed aside by ‘inplanation’. Is it possible to see too much in a work of art? Of course this is possible, the literature on Bosch of the past one hundred years offers numerous examples. Moreover, one may humbly wonder whether the attribution of different, diverging explanations to one particular Bosch detail is the result of the fact that we do not really understand it. We look at medieval paintings through the glasses of our own ignorance, Roger Marijnissen liked to reiterate. And as Marijnissen also pointed out: is it not better to keep silent in such cases, instead of blathering (zwijgen in plaats van zwetsen)? It stands to reason that when an author not only attempts to look through the glasses of Bosch’s contemporaries but also through the glasses of virtual viewers living after Bosch, this whole issue is raised to the square.

Whether it is called Mehrdeutigkeit, contingency, or amphibolism, as long as such an approach is not a safe-conduct to your-guess-is-as-good-as-mine and uses solid and verifiable arguments for each thesis and hypothesis, it is only fair that people read it or listen to it in an attentive, be it critical way. The Epiphany of Hieronymus Bosch is definitely a very well-edited book, marked by a high academic standard. In order to reconstruct the world view of two generations (Bosch’s generation and the one after him), Higgs Strickland has done an admirable amount of field work, resulting throughout her book in elaborate and highly informative surveys of a whole range of medieval and early modern themes and issues (the worshipping of the Three Magi, the End of Days expectation, the Antichrist legend, the attitude towards blacks, Turks, and Jews, the Mass of St Gregory, the Modern Devotion, leprosy, the arrival of syphilis in Europe, the struggle between Catholics and Protestants, and so on). But when it comes to applying this collected material to Bosch’s Prado Epiphany, I am less enthusiastic. In his review Al Acres wrote: ‘Readers will resist some of the specific associations she proposes, but will find it difficult to dismiss their viability for many sixteenth-century minds’. Between these lines, Acres courteously offers a double opinion on the book: Higgs Strickland’s cultural-historical documentation is solid and fascinating, but when she writes about Bosch this is far less the case.

In a review that was also published online, Kimberlee Cloutier-Blazzard calls Higgs Strickland’s monograph a ‘provocative new book’. She points out that in the past Higgs Strickland has already written a lot about what anthropologists call ‘the Others’ (i.a. in her book Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art, published in 2003 – the word ‘Others’ als features in the subtitle of The Epiphany of Hieronymus Bosch), and that she approaches Bosch’s Epiphany from this same perspective. It is true that throughout the monograph the opposition Christians / non-Christians is continuously hinted at, resulting in the discovery of signs of enmity and aggression everywhere (‘enmity’ another word apparently indebted to Koerner’s approach of Bosch). Cloutier-Blazzard notes: ‘Curiously, in light of her ultimate desire for allowing visual ambiguity (amphibolism), Strickland nearly always argues from a partcularly pessimistic and negative angle, hinged on the appearance of the strange pale figure, shepherds, black Magus, and the three “armies” in the background as”other”’. The last sentences of her review are: ‘In the end, I simply cannot find the overwhelming tide of xenophobia and racism in the Prado Epiphany suggested by Strickland. While the period evidence of exclusion she marshals is considerable, and its study is invaluable, I do not see it insistently or convincingly echoed in the mysteries of Bosch’s poetic pictorial language’.

As has become apparent from the personal notes (in italics) in the above summary of the book, I concur with Cloutier-Blazzard. I really think Higgs Strickland has wanted to see too much in Bosch’s Epiphany. Except for the pale figure in the stable (most probably the Antichrist) and his Jewish conspirators, I can find little ‘enmity’ and ‘aggression’ in the triptych, and least of all when it comes to the Three Magi. In my opinion, the author hineininterpretiert (overinterprets) other details as well: the shepherds around the stable are only there to have a look at the new-born baby, the three armies in the background are simply the armies of the Three Kings on their way to meet each other, Jerusalem is Jerusalem, Joseph is drying the Christ Child’s diapers, and the dancers are happy because the Saviour is born. Admittedly, the wolves in the right interior panel are aggressive, but unfortunately this is a detail that Higgs Strickland finds hard to explain. A case of ‘it is better to keep silent than to blather’?

In her review Cloutier-Blazzard sums up a number of other minuses of Higgs Strickland’s argument, i.a. the almost complete lack of Dutch contemporary textual sources (and each time Middle Dutch is quoted, spelling errors abound), and the description of the medieval attitude towards blacks as univocally negative (whereas one of the Three Magi is a black saint, and there were more black saints, such as St Mauritius). I would like to add another small critical rmeark to this. Higgs Strickland is often inclined to give her speculative interpretations more credibility by referring to other Bosch authors. But is what these other Bosch authors have said always correct? An illustrative example of this can be found on page 248. When the author identifies the headgear of the pale figure in the stable as a Judenhut (Jew’s hat), she writes: ‘This interpretation is strengthened by Bosch’s investment of metallic hats with Jewish meanings in other paintings. For example, a metal helmet worn by the barrel-riding figure in the Allegory of Gluttony has been interpreted as a Judenhut which operates as a sign of Jewish avarice in this context’ (underlined by me). This interpretation does not seem very fortunate: the Allegory figure wears a funnel on his head, this figure has nothing to do with Jews, and the context refers to gluttony rather than to avarice. Moreover, the source reference in footnote 72 (p. 260) says: ‘On the Judenhut identification, see Garrido and Schoute, Bosch at the Museo del Prado, 308’. But this book (see Garrido/Van Schoute 2001) only has 277 pages, so page 308 does not exist. Weird.

Other reviews

[explicit 10th February 2020]