Ilsink 2010

“On Three Drawings by Jheronimus Bosch: The Field has Eyes and the Wood has Ears, The Treeman, The Owls’ Nest” (Matthijs Ilsink) 2010

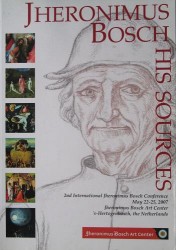

[in: Eric De Bruyn and Jos Koldeweij (eds.), Jheronimus Bosch. His Sources. 2nd International Jheronimus Bosch Conference, May 22-25, 2007, Jheronimus Bosch Art center, ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands. Jheronimus Bosch Art Center, ’s-Hertogenbosch, 2010, pp. 174-188]

Bosch’s drawings meant a radical break with the usual late medieval drawing practice in which a drawing almost always had the character of a model sheet. With Bosch the creative work of an artist as someone who produces new, innovative images comes to the fore: his drawings are works of art in their own right. In this contribution Ilsink focuses on three of Bosch’s most famous drawings that are generally considered to be authentic and together form the core of Bosch’s drawn oeuvre.

Ilsink assumes that the drawing The Field has Eyes and the Wood has Ears (Berlin) functioned in the immediate circle of the master himself. His starting point is the 1937 article in which Otto Benesch called the drawing ‘ein eingekleidetes Selbstbildniss’ (a disguised self-portrait). According to Ilsink the drawing not only depicts the proverb ‘the field has eyes and the wood has ears’, but at the same time it refers to Bosch’s identity as a citizen of ’s-Hertogenbosch and as an artist. Dead trees and owls are not only the main characters in the three drawings under discussion here, but are items that constantly return in the work of Bosch and as such they always refer to evil things. Furthermore, an owl was also called boschvoghele (forest-bird) in Middle Dutch, which is why we can also call it a ‘Bosch-bird’, and a variant of the Middle Dutch word for ‘evil’ was bôs. So the name and the connotation of the owl lead us back to the name of Bosch. The fox and the rooster likewise refer to evil things.

In late medieval heraldry the name of the city of ’s-Hertogenbosch (literally: the duke’s forest) was sometimes represented by means of a picture-puzzle: for example a heart (hert in Middle Dutch), a pair of eyes (ogen) and a single tree (referring to a bosch = forest). Because the Berlin drawing shows ears, eyes and trees Ilsink suggests to read the drawing as a picture-puzzle: ‘hoort-ogen-bosch’ (hears-eyes-forest). Moreover the drawing is built up like an impresa, an emblem describing and representing the one who carries it. Bosch even added the motto that normally accompanies such an emblem. It can also be seen as a speaking coat of arms, a self-invented heraldic shield containing elements that revolve around the name of its holder. By turning a common proverb into an uncommon, witty image Bosch presented himself as an original artist of high genius, and more particularly as an artist from ’s-Hertogenbosch. He let his own art represent himself.

In the drawing The Treeman (Vienna) we see a deer (hert in Middle Dutch) and a tree: can these elements also be read as a picture-puzzle referring to ’s-Hertogenbosch? The owl attacked by other birds is again a ‘boschvogel’. In the Rotterdam drawing The Owls’ Nest Bosch also used owls and dead trees, two motifs referring to ‘the essential Bosch’.

This text is a (too) severely condensed version of the first chapter of Ilsink’s dissertation, which was published commercially in 2009 (see also Ilsink 2009 for further comments).

[explicit 29th April 2012]