Jeffrey 1973

“Bosch’s ‘Haywain’: communion, community, and the theater of the world” (David L. Jeffrey) 1973

[in: Viator, volume 4 (1973), pp. 311-331]

[Also mentioned in Gibson 1983: 98 (E152)]

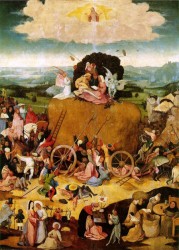

In this article Jeffrey attempts to place the Haywain triptych in the liturgical tradition of the altarpiece. According to him the central panel with its hay symbolism is more than a proverbial reference to greed and the vanities of the world. The all hay expression doesn’t show a clear relationship with (among other things) the music-making group on top of the haywain. Furthermore this group is characterized by peace and harmony and contrasts with the restlessness and chaos of the people around the haywain. That is why the first group is meant to be a comment on the second group, by referring to ‘community’ and ‘Love’. In the Middle Ages music-making could also refer to physical love and this is the case with the kissing couple on top of the haywain, which is being accompanied by the man hiding behind a bush (it can be noticed, though, that neither this couple nor this man are making music). In other words: on top of the haywain a conflict is going on between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ music, between Celestial Love and earthly, carnal love: it is as if we see a scene from a pageant or a play.

According to Delevoy Bosch participated in stage performances and processions in his home town. It stands to reason then that these (religious) plays and processions influenced his paintings, especially the feast and procession of Corpus Christi. The civil and ecclesiastical officials participating in the central panel’s haywain procession remind us of the hierarchical parades that were typical of Corpus Christi processions. The only difference is that with Bosch the powers of the world are not following the Host, but that is precisely what Bosch intended to say. When designing his panel Bosch not only thought of the Corpus Christi liturgy, but also of a Scriptural text (Jeremiah, chapter 23) where a distinction is made between the wheat and the chaff. Bosch wanted clergy and laymen to examine their hearts before participation in Holy Communion (the triptych was placed on top of an altar). This is confirmed by Christ who appears in the sky in the same way in which he will appear at the Last Judgment. The ‘evil’ music on top of the haywain refers to sinfulness and earthly vanities – as does the piper at the bottom of the central panel – whereas the ‘good’ music refers to the possibility of repenting and being saved by Christ.

The ‘troubled Pilgrim’ on the triptych’s exterior is attacked by a dog: probably a metaphorical reference to the clergy, often neglecting its task and thus being an obstacle rather than a help for man as a pilgrim on his way to community with Christ. Perhaps the triptych functioned as an altarpiece in a chapel of one of the local fraternities in ’s-Hertogenbosch, possibly even in the chapel of the Fraternity of Our Lady or of the Brethren of the Common Life.

Jeffrey makes some correct observations (for example when he points out that the left interior panel refers to the origin of sin, the right interior panel to the future punishment at the Last Judgment and the central panel to contemporary times) but his thesis that the music-making group on top of the haywain is a positive reference to the road of Salvation, is untenable because a devil is participating in the music-making of this group. The article also contains a number of minor observations and interpretations that are manifestly wrong (an example: the owl in the central panel is said to be defecating…). Jeffrey’s interpretation of the exterior panels is very weak (the dog as a symbol of the bad clergy). It has not been proven that Bosch participated in processions and stage performances and influence from the liturgy of Corpus Christi is possible but hard to prove and not all that relevant. Neither is the Scriptural text about the wheat and the chaff: the central metaphor of the central panel is hay and in this respect quite a number of obviously more relevant Scriptural texts can be quoted.

[explicit]