Kenis 2001

De Tuin der Kennis 1498-1998 (Jan Kenis) 2001

[Esopus-Uitgevers, s.l., 2001, 137 pages]

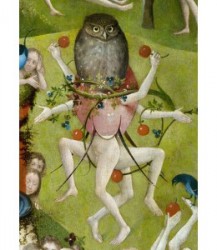

Jan Kenis was a Belgian civil servant mainly active in the field of art and culture. Part of his leisure time he spent on a study of Jheronimus Bosch’s so-called Garden of Delights triptych. Before he could round off this study, Jan Kenis passed away, in 1997. Two of his friends, Joannes Késenne and Stefan Beyst, took it upon themselves to adapt and publish Kenis’ posthumous texts. In 2001 this book was published, carrying the remarkable title De Tuin der Kennis 1498-1998 [The Garden of Knowledge 1498-1998].

Kenis’ approach of Bosch and his Garden of Delights is completely new. His starting point is the figure of Jacob van Aelmanghien, a Jew who, according to local archival sources, was baptised in ’s-Hertogenbosch in 1496 and whose godparent was Philip the Fair. The converted Jew’s Christian name became Philips van Sint-Jan [Philip of St John], but soon after he turned away from the Church again. Bosch scholars know this Jacob van Aelmanghien thanks to the German author Wilhelm Fraenger (+1964) who concocted a completely fictional biography of this historical figure, based on the works of Bosch. According to Fraenger Van Aelmanghien was the leader of a heretical sect, the Adamites, and Bosch is supposed to have painted a number of his works for this sect.

But Kenis does not refer to a heretical sect. According to him Jacob van Aelmanghien is the same person as Jochanan Alemanno (Alemanno is the Latin version of the name Askenazi, the Hebrew word for Germany, and in Middle Dutch Germany was called Aelmanghien), a Jew of German origin who is attested in Padua in 1486, in the environment of the Italian humanist Pico della Mirandola. Alemanno worked together with Pico who published his Heptaplus in 1489, an elaborate comment on Genesis, mingling neoplatonic and cabbalist ideas. According to Kenis Alemanno came to the Netherlands between 1490 and 1500, where he met and thoroughly influenced Bosch. To such a degree that the Garden of Delights can be interpreted with the help of the cabbala. Bosch is said to have been mainly inspired (thanks to Alemanno/Van Aelmanghien) by the major text of the cabbala, the thirteenth-century book Zohar.

That Bosch used cabbalist ideas in his Garden of Delights is a revolutionary and ambitious thesis. When an author suggests such a surprising approach, it may duly be expected that he tries to convince the reader with very strong arguments or at least with keen observations that are worth considering. Unfortunately, it has to be pointed out from the start that De Tuin der Kennis completely fails in this respect. We will try to justify this harsh judgment as objectively as possible.

A first observation: Kenis’ book has not a single footnote and lacks a bibliography, which of course makes a rather poor impression from the very start. This impression is confirmed as soon as one notices in which irresponsible way the author deals with his (unmentioned) sources in the first pages. Pages 18-19, for instance, correctly signal that the Italian canon Antonio de Beatis saw the Garden of Delights in the Brussels palace of count Henry III of Nassau in 1517. Kenis claims that De Beatis jotted down in his travel journal that the triptych was hanging devant la cheminee (above or facing the fireplace). However, this information is not given by De Beatis’ travel journal at all, it can be found in the inventory of the Nassau court that was made up in 1568, by order of Alva [compare Vandenbroeck 2001c: 88 (note 7)]. This could be considered a minor error, were it not that the author concludes from this that in 1517 (one year after Bosch’s decease) the triptych was not located in the palace’s chapel and so that it was not intended as an altarpiece. The truth is that we do not know where the triptych was located inside the palace in 1517 and the question whether the Garden of Delights was or was not intended to be an altarpiece, remains open for discussion.

On page 25 Kenis quotes (with inverted commas) the Spanish author José de Siguença who devoted a number of pages to Bosch in 1605. He has the Spaniard say that Bosch painted satires on the sins and folly of man: That is how his ‘Seven Deadly Sins’, his ‘Garden of Delights’, even his ‘Cutting of the Stone’ and ‘Conjuror’ or whatever these paintings may be called should be interpreted. But this last sentence (put in italics by us) is not to be found in Siguença’s text and has been added by Kenis himself [compare Tolnay 1965: 401-404 for the original text]. Siguença never mentions a painting called The Cutting of the Stone or The Conjuror and the (modern) title The Garden of Delights did not even exist in 1605. If you deal with your sources in such a loose way, you are bound to make an unreliable impression.

Second observation: only the last fourty pages of this book deal with the Garden of Delights triptych. The twenty preceding pages focus on Bosch’s Haywain triptych and the first eighty pages try to describe the relation between Bosch and late-medieval Burgundian culture. These three subdivisions have a total lack of structure in common. The argument continuously jumps from one subject to another and loses itself in elaborations in and out of season, resulting in the irritated reader’s question what all this has to do with Bosch, let alone with the Haywain or the Garden of Delights. The first part, for instance, deals with the Holy Grail, the festive culture of the Burgundian dukes, the Lamb of God altarpiece by the Van Eyck brothers, the Brabantine devotional author Dionysius the Carthusian and the hunt for witches in Arras, but later in the book none of these things seems important for a better understanding of the two Bosch triptychs that are being discussed.

The only explanation for this chaotic structure can be that the text which is being posthumously published here only boiled down to more or less (but more often less than more) coherent annotations and that the two adaptors have to tried to glue these pieces together to the best of their ability. Very telling in this respect is that the last chapter (or more correct: the last section) is lacking, apart from its title. In her preface Liesbeth Jonckheere is right when signalling that the book is unfunished, but she mildly adds that every text is worth reading and being interpreted and that, according to postmodern fashion, the reader is the real writer of this book. Such a statement can maybe be true in the case of a novel or a poem but surely not in the case of a serious study about late-medieval art that – to top it all – pretends to offer a revealing interpretation of a very difficult painting!

All this inevitably leads to the rather painful question whether the adaptors have delivered Jan Kenis a service (no doubt intended as a posthumous tribute) by publishing one of his Bosch books. If these texts, unfinished or not, had offered remarkable or keen observations, the answer to that question could have been affirmitive. But the contrary is true. The identification of the Italian Jochanan Alemanno with the ’s-Hertogenbosch Jacob van Aelmanghien, for instance, is only made plausible by means of the two names. But on page 64 the author himself claims that the name Askenazi (with its Latin form Alemanno) was known in the whole of Europe and the Middle East at the end of the fifteenth century. And moreover: isn’t Jochanan a Hebrew variant of Johannes instead of Jacob?

The second part of the book offers a not very convincing astrological interpretation of the Haywain triptych. The painting is said to represent the influence of Saturn and the central panel is claimed to depict the horoscope of the End of Times. In his analysis Kenis continuously commits observational errors (the growling dog in the exterior panels is said to guard the horse’s skeleton, some scenes around the haywain should be interpreted in a peaceful or pleasant way, the sitting woman to the left is said to give alms to a sleeping beggar…), he considers hay a symbol of time referring to the end of all living things (a meaning that can nowhere be found in late-medieval culture, see De Bruyn 2001a) and in the yellow rectangle of the haywain he draws some far-fetched lines that in the end make up a square and twelve triangles: supposedly the horoscope as drawn up by medieval astrologers. Together these pages are a nice specimen of Hineininterpretierung.

Kenis’ chaotic approach of the Garden of Delights in the last part is equally unconvincing and far-fetched. All the time, the author relates quotes from cabbalist texts to certain details of the triptych but this never leads to an all-round, harmonic intepretation of the painting as a whole. None of the texts quoted by Kenis give the reader the impression that Bosch was inspired by them, although the author categorically writes on page 124: ‘The person who has read the Zohar, knows that Bosch was inspired by descriptions from this book when he designed his garden’. The descriptions literally and elaborately quoted by Kenis are definitely not capable of convincing the reader of a cabbalist meaning of the Garden of Delights triptych.

De Tuin der Kennis also offers the reader a number of illustrations with comments. In some of these comments the Hineininterpretierung is pushed even further than in the normal text. In this respect, what tops it all is the illustration-with-text on pages 94-95, where in a drawing of ten men (attributed to Bosch) the author recognizes Bosch and Van Aelmanghien himself in the last row. At that moment we have largely crossed the borderline of what can be accepted from a scientific point of view and we travel through a region where vicarious shame defines the climate. All the illustrations are presented without any reference and together with the uncountable printing errors and the sloppy layout this casts another slur on this publication, for which in this case not the author himself but the adaptors are responsible. What is, for instance, the meaning of the years in the subtitle (1498-1998)? The colour illustration of the Garden of Delights on the backflap dates the triptych 1504, but even this year is nothing but a random guess, because the dating of the triptych is as yet uncertain. 1998 probably refers to the year in which the author passed away, but the backflap tells us that this happened in the year 1997…

It may sound rather arrogant and in this specific case even extremely tactless, but perhaps both adaptors should have decided not to publish this collection of texts. In any case, De Tuin der Kennis 1498-1998 is an incomplete, but unfortunately also a very imperfect and in fact even a redundant book.

[explicit]