Schwartz 2016a

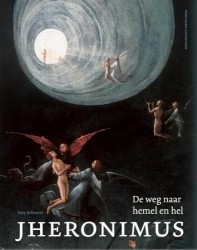

Jheronimus Bosch – The Road to Heaven and Hell (Gary Schwartz) 2016

[Overlook Duckworth, New York-London, 2016, 256 pp.]

[Dutch version: Gary Schwartz, Jheronimus – De wegen naar hemel en hel. Fontaine Uitgevers, Hilversum, 2016, 256 pp.]

As was to be expected, quite a number of new books on Bosch (who died in 1516) were published in 2016. Jheronimus Bosch – The Road to Heaven and Hell by American art historian Gary Schwartz is not a groundbreaking publication and cannot really be called ‘required reading for Bosch experts’. Nevertheless, it is one of the finest and soundest general introductions to Bosch that have appeared on the market recently: it is highly informative, has got plenty of beautiful and well-chosen illustrations and there is hardly a page that is not interesting.

The book is divided into seven parts: the world of Bosch (pp. 16-35), the life of Bosch (pp. 36-53, with a survey of the archival documents on Bosch on pp. 48-53 ), Bosch as an artist (pp. 54-81, including notes about Bosch’s sources and patrons), the drawings (pp. 82-103), the paintings (pp. 104-205), the heritage of Bosch (pp. 206-225) and a short chapter on the Bosch Research and Conservation Project (pp. 226-229). In part 5 the paintings are not discussed in chronological order but according to subject matter: Christ, the saints, the End of Days and the life and fate of humankind with special focus on the Garden of Delights. In the preface (p. 15) the author announces that he follows the chronologies established by Stefan Fischer for the paintings and by Fritz Koreny for the drawings (although on pp. 80-81 he also warns the reader that there is still a lot of disagreement among scholars about this matter).

According to Schwartz Bosch was an artist with a unique imagination whose art conveys a basically Christian message. Bosch’s images easily call to mind the proverbs, stereotypes and folk tales of his native language (Middle Dutch), although his works were also appreciated by patrons and collectors who spoke another language (French, Italian, Spanish). Schwartz also points out that the art of Bosch is often humorous, that alchemy plays a certain role in it and that Bosch’s social context is important in order to understand his oeuvre. As has been done by other authors as well recently, Schwartz points out affinities between Bosch and the writings of Dionysius the Carthusian (pp. 35 / 154 / 169).

One of the praiseworthy things in this book is that Schwartz does not shy away from offering his own opinion about certain issues and matters, although it has to be admitted that the arguments that are supposed to support his opinions are mostly rather superficial and sometimes even weak. Some examples of the cases in which Schwartz defends a personal view.

- Koldeweij and Ilsink interpreted the The Field has Eyes drawing (Berlin) as a rebus on the name of ’s-Hertogenbosch and even on the artist Bosch himself. Schwartz kindheartedly calls these interpretations ‘fun speculations’ (p. 85).

- Schwartz believes the Hellish Landscape drawing (private collection), which emerged in 2003, is an original Bosch drawing, disagreeing on this with Koreny (p. 90-91).

- The so-called ‘fourth king’ in the Prado Adoration of the Magi is claimed to be a figure anticipating Christ as King of the Jews. A confused and rather implausible interpretation (p. 117). It gets even more confused when a figure in the exterior panels of the Bruges Last Judgment triptych is drawn in (p. 156).

- Equally weak is the assertion that the boy with a whirligig in the Vienna Carrying of the Cross panel is not Christ because a boy with a whirligig can also be seen in the exterior panels of the Lisbon Saint Anthony triptych (p. 127).

- Fischer related the scene in the upper left interior panel of the Lisbon Saint Anthony triptych to a passage in the saint’s vita in which angels lift Anthony up in the sky and take him to heaven whereas devils want to prevent this. Schwartz correctly observes that no angels can be seen in Bosch’s scene (p. 143).

- According to Schwartz the saint in the right exterior panel of the Vienna Last Judgment is Saint Bavo. Koldeweij’s hypothesis (it is Saint Hippolytus) is not mentioned (not even in the bibliography) (p. 160-161).

- On page 189 Schwartz offers a new (unconvincing) interpretation of the Prado Cutting of the Stone panel: its message is said to be that members of the Order of the Golden Fleece are mortals just like everyone.

- Schwartz is not convinced that the chin of the female protagonist in the Crucified Female Martyr triptych (Venice) bears traces of beard (p. 239). He also disagrees with Vandenbroeck’s interpretation of the four roundels in the Rotterdam Flood panels as episodes in the story of Job (p. 239).

- In an earlier publication [Schwartz 1997: 80] Schwartz wrote that the people in the central panel of the Garden of Delights triptych ‘are on their way to hell’. He now disagrees with this earlier interpretation of his and sees the central panel as a vision of the world as it could have been if Adam and Eve had not sinned (pp. 199 / 201). This automatically implies that Schwartz does not see any allusions to homosexuality in the central panel.

These examples clearly show that Schwartz is not just a copier of other people’s ideas: he likes to think for himself. But on page 240 he writes: ‘I have not attempted to incorporate, let alone compete with, the magisterial contributions of Paul Vandenbroeck’. It is a fate that has been bestowed upon Vandenbroeck’s extensive texts on Bosch more than once: they are called ‘magisterial’, but hardly anyone wants to (can?) engage upon a dialogue with them. Why, one wonders?

Unfortunately, Schwartz’ book has some (minor) errors and imperfections. Some examples.

- On page 43 the Middle Dutch proverb als die buyc opgaet soe bract dat spelken wt is translated into English as ‘when the flesh rises the game begins’. This should be: ‘When the belly swells up the truth is uncovered’ (referring to the pregnant state of a girl or woman).

- Page 112 points out Judas who has committed suicide in the upper right exterior panel of the Prado Adoration of the Magi and then also mentions ‘a figure dangling upside down in the sky, his legs wrapped around a pole held by a flying, insect-like demon with a burning head’. Schwartz does not seem to be aware that this is Judas’ soul carried to hell by a devil. If he is aware of it, he overestimates the general reader by not explaining this detail.

- On page 151 the tree half dead, half living in front of Saint Hieronymus in the Venice Hermit triptych is called a ‘threatening’ motif. Apparently, Schwartz is not aware that this motif is a symbol of Christ’s resurrection. Although in an endnote on page 237 he seems to utter his doubts about the validity of the methodology of Bax and De Bruyn, Middle Dutch texts could have informed him about this symbolism.

- The correctness of the title of the panel from the Venice Visions of the hereafter wings represented on page 168 (Purgatory) is very implausible. More likely is the title Hell.

- Page 170 says about the Venice Earthly Paradise wing: ‘No longer does beast eat beast, as in the state of nature’. But in the background a lion is eating a deer!

- On page 184 the boat in the Paris Ship of Fools panel is called ‘a rudderless boat’. But this boat has a large ladle functioning as a rudder!

- On page 219 the words of the song in the Concert in an Egg panel are called ‘not very appropriate for the theme of the painting’. But they are! The song is a (silly) love-song and the theme of the painting is licentious merrymaking.

- In a number of cases, when he does not understand what Bosch painted, Schwartz seems a bit too rash to conclude that Bosch did not want to be understood. Examples of this on pages 117 (the ‘fourth king’ of the Prado Adoration of the Magi), 144 (the ‘secondary’ scenes in the Lisbon Saint Anthony triptych) and 179 (the pedlar in the exterior panels of the Haywain triptych). As Marijnissen has so often said: we look at late medieval paintings through the eyes of our own ignorance.

- And finally a pure trifle. Of course, we all know that a rose by any other name would smell the same. And yet. On page 15 Erwin Verzandvoort’s name is spelled as ‘Erwin Zandvoort’ (both in the English and in the Dutch version). My own name (Eric De Bruyn) is continuously spelled as ‘Eric de Bruyn’. In the index on page 250 it is even spelled as ‘Erik de Bruyn’ (both in the English and in the Dutch version).

There are also some minor differences between the English and the Dutch version of the book.

- The sentence ‘the tree on the right is made inhabitable with a giant crock lived in by little people such as the one climbing the highest branch’ in the English version (p. 133) is lacking in the Dutch version (p. 133).

- In the section on the Garden of Delights endnote 10 is lacking in the English version, but not in the Dutch version (pp. 201 / 240).

- Page 228 of the English version says that Bosch was buried on 8 August. Page 233 of the English version and pages 228 / 233 of the Dutch version have the correct date: 9 August.

- Then again, the endnotes belonging to the section ‘Jheronimus had more than one calendar’ on page 237 are lacking, both in the English and in the Dutch version.

Obviously, we are all familiar with Titivillus, the printer’s gremlin.

Reviews

- Nik de Vries, "Gary Schwartz", in: Bossche Kringen, vol. 3, nr. 3 (May 2016), pp. 64-65 [this text is not a real review but a two-page notice].

[explicit 23rd August 2016]