Traeger 1970

“Der ‘Heuwagen’ des Hieronymus Bosch und der eschatologische Adventus des Papstes” (Jörg Traeger) 1970

[in: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 33. Band (1970), Heft 4, pp. 298-331]

[Also mentioned in Gibson 1983: 99 (E157)]

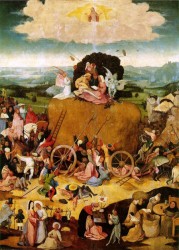

The fact that the Haywain triptych has a left interior wing showing Eden and a right interior wing showing Hell is an iconographic parallel with a Last Judgment triptych (see Bosch’s Vienna Last Judgment triptych). Although the left interior wing of the Haywain is primarily intended to depict Earthly Paradise at the time of the Fall of Man, at the same time it refers to Earthly Paradise as the future location of the blessed on the Day of Judgment.

In the left interior panel it is not God the Father who judges the rebel angels, but God the Son. Bosch mixed two ideas: the Fall of the Rebel Angels with God as almighty lord and the Last Judgment with Christ as judge. In the Middle Ages the Fall of the Rebel Angels was not only interpreted as the origin, but also as the exemplary punishment of Evil. There was an analogy between God’s punishment of the unfaithful angels and the punishment He had in store for sinners. In the central panel there are also references to the Last Judgment. The devil who is blowing an instrument refers to the fanfare announcing the Last Judgment and the praying angel is playing the part of advocate, which is normally reserved for the Holy Virgin or St John the Baptist.

In spite of this Last Judgment scheme of the triptych Earthly Paradise in the left interior wing is not the future one, but the one that has been lost forever. Due to the Fall of Man human life has become a road to Hell. Christ’s sacrifice and death at the cross have not been able to save humanity: Christ has lost His control over the earth (which is why the gesture of his arms expresses worry and disappointment) and humanity is obsessed by the hay. An alternative for the hay hunting is nowhere to be seen. In the Haywain Bosch painted a pessimistic interpretation of Predestination.

This part of Traeger’s argument is untenable. He erroneously interprets Christ’s gesture as a sign of despair whereas it is actually a gesture of comforting and forgiving (because of Christ’s sacrifice at the cross – He ostentatiously shows the wounds in His hands and side – sinful humanity can still be saved). This means there is definitely an alternative for the hay hunting (to follow Christ and to ignore the earthly vanities) and this alternative is also demonstrated by the pedlar in the closed wings. These closed wings are likewise interpreted in an erroneous way by Traeger (see infra).

The high officials behind the haywain do not refer to historical persons, except for the pope: he looks very much like portraits of Alexander VI as we know them from late-medieval coins. This identification agrees with the dating of the triptych in the years between 1485/90-1502 (Alexander VI was pope from 1492 till 1503). Traeger then claims that the interior panels of the triptych show no unity of space, making it possible that certain persons from the central panel reappear in the other panels (an argument that does not make sense as in the left interior panel – with Earthly Paradise as unity of space – Adam and Eve appear three times…). According to Traeger the pope behind the haywain is the protagonist of the central panel. This pope is the largest figure of the central panel, he is the only leader who rides a grey, his right hand points out the direction that has to be followed and at the same time blesses the hay hunting and he is also the only person who can be identified. We may duly expect therefore that he is also the protagonist of the right interior panel. Traeger recognizes him in the naked figure riding an ox (a motif that – as far as he knows – is unique in the oeuvre of Bosch). Obviously Traeger does not consider the Bruges Last Judgment triptych an original Bosch.

The cloth behind the naked figure on the ox is identical with the purple and pink ‘cappa rubea’ of the pope behind the haywain and at the same time refers to the ceremonial ‘naccum’, the red cloth that traditionally covers the pope’s horse. The pitcher and the little basket hanging from the ox’s neck, the lance piercing its rider and his headgear are also associated with papal attributes. In this context they have been diabolically distorted as a punishment for the pope. Traeger then signals that riding an ox belongs to a medieval tradition of punishing and mocking, and also popes could fall victim to this practice.

When Traeger discusses this tradition, he mentions donkeys, camels and pigs, but no oxen. Traeger’s interpretation of the pope as protagonist of the central panel and his identification of the ox-rider as a pope in hell make a very far-fetched and arbitrary impression.

Traeger even takes things a step further: the key to the interpretation is not what iconographically speaking unites the triptych with the Last Judgment, but the way in which the triptych differs from the Last Judgment. The closed wings may help here. The vagabond, who is moving from left to right just as the people in the central panel, represents man on the road through a sinful world. The closed wings further refer to Judgment Day (the staff) and to death (gallows and skeleton). The closed wings have the same iconographic meaning as the interior panels: man is on his way to Hell, a stay in Paradise is no longer possible.

Traeger then arrives at the last part of his argument. Influence of the ‘trionfi’ on the design of the central panel has already been signalled by others. The major forms of the papal trionfi were the Adventus (the glorious entry of the pope in a city) and the Profectio (the festive leave of the pope). In the right interior panel the pope is confronted with a diabolical Adventus, and the central panel shows a parallel with the Profectio because here the pope takes his leave from Paradise in a triumphant way. Finally Traeger also identifies the pope behind the haywain as the Antichrist (Cranach also painted pope Leo X as the Antichrist). Traeger summarizes his interpretation of the Haywain as follows: the world is governed by the powerful hay and because of this the Antichrist, the earthly viceroy of Christ, is in charge (whereas Christ abdicates His power).

This thesis is far-fetched and untenable. Traeger’s article has three interesting observations, though: the structure of the Haywain triptych resembles the structure of a Last Judgment triptych, at the top of the left interior panel it is not God but Christ who judges the fallen angels and the pope behind the haywain looks like Alexander VI. About this article, see also De Bruyn 2001a: 59-60.

[explicit]