Van Waadenoijen 2010

“The Bible and Bosch” (Jeanne van Waadenoijen) 2010

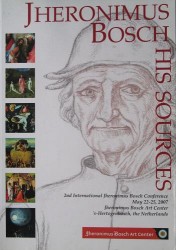

[in: Eric De Bruyn / Jos Koldeweij (eds.), Jheronimus Bosch. His Sources. 2nd International Jheronimus Bosch Conference, May 22-25, 2007, Jheronimus Bosch Art Center, ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands. Jheronimus Bosch Art Center, ’s-Hertogenbosch, 2010, pp. 334-345]

It is the author’s intention to show that a close confrontation of Bosch’s works with the Bible proves that Bosch was well acquainted with the Bible and that the Bible is essential for a correct apprehension of his paintings. After having summed up some Bible-related details from Bosch’s works that were already signalled in the past, Van Waadenoijen gives a list of other scriptural quotations that were not recognized. In the Madrid panel with The Seven Deadly Sins the Avaritia scene refers to Isaiah 1: 21-30, the Gula scene to Proverbs 22: 6 and the Sloth scene to Proverbs 19: 15/24 (the sleeping man hiding his hand in his bosom). In the Prado Adoration of the Magi some Old Testament scenes have a typological meaning, such as the representation of Abner before David on the orb carried by the black king which is a prefiguration of the adoration of the magi. The so-called Fourth King in the same triptych is the Jewish Messiah as described by Isaiah and a prefiguration of Christ. His companions show that the Jews rejected the true Messiah. The message of the column with Old Testament scenes on the central panel of the Lisbon St. Anthony is: beware of the devil, believe in Christ and do not sin (Moses and the bunch of grapes being prefigurations of Christ). The scene to the left of the column does not represent a black mass but reminds us of the fact that the tavern is the devil’s church. The little monster in a children’s playpen (right wing) refers to the sinner: in the Bible children are sometimes associated with negative things, for example in Corinthians 14: 20.

Using other biblical quotations Van Waadenoijen explains the Judith slaying Holofernes scene in the Venice St. Jerome as an image of chastity overcoming lust, the unicorn as the repentant sinner and the column-like structure with sun, moon, stars and a kneeling figure as a scene of idolatry. As for the Rotterdam Flood panels: the so-called left wing with monsters in a landscape represents the world right before the end of time. In the Ghent St. Jerome the saint is represented fighting against his carnal desires, suggested by the darkness and decay around him. The Gospel quotation about the foxes having holes and the birds having nests is important here. The lush landscape in the background symbolizes the land the saint is hoping to reach by doing penance for his sins and reminds us of Psalm 22 (23).

When we compare these works with similar paintings by Bosch’s contemporaries, it is clear that Bosch’s originality unfolds in the details. At the same time these details show that Bosch is a child of his age because more than the works of his contemporaries Bosch’s paintings resemble the sermons, treatises and literature of the period, built up from and abounding in biblical quotations.

No doubt Van Waadenoijen’s starting point is correct: the Bible was an important source for Bosch. In trying to prove this Van Waadenoijen sometimes exaggerates and offers rather far-fetched interpretations, but ever so often her biblical knowledge is admirable and leads to brilliant observations. The result of this is that what she writes about each particular Bosch scene has to be carefully double-checked before deciding whether it makes sense or not.

[explicit 6th August 2012]