Van Wamel 2021

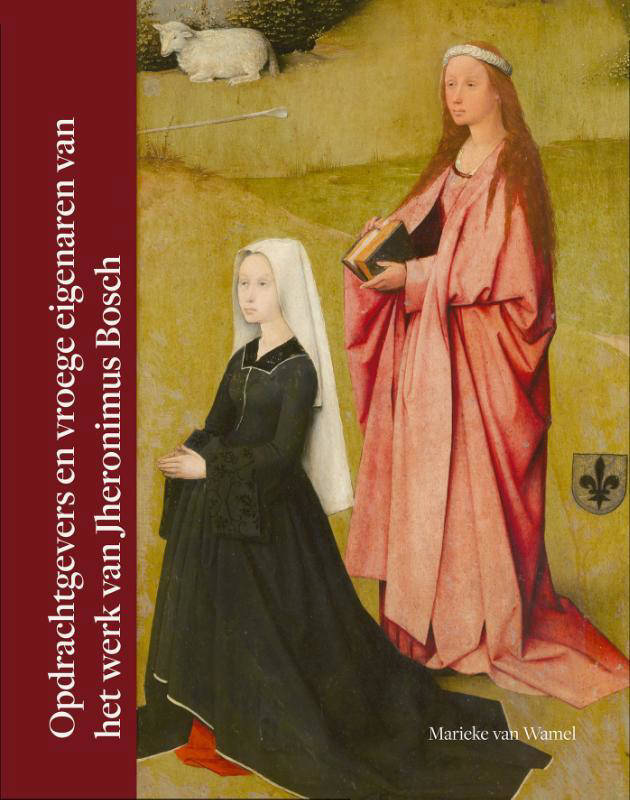

Opdrachtgevers en vroege eigenaren van het werk van Jheronimus Bosch (Marieke van Wamel) 2021

[SPA-uitgevers, Nijmeegse Kunsthistorische Studies – vol. XXVII, Zwolle, 2021, 315 pages]

On 20th September 2021 Marieke van Wamel was awarded her Ph.D. in Art History at the Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. Jos Koldeweij and Ron Spronk were the supervisors (promotor), Matthijs Ilsink was the co-promotor (third supervisor). This is the commercial edition of her dissertation, presented to the reader with an attractive layout. The introduction announces that this study is dedicated to the commissioners and early owners of the art of Bosch, all of them contemporaries of the painter or members of the following generations (up to around 1600) and belonging to three varying social ranks: the urban burgher elite, ecclesiastical institutions, and the high nobility. Almost four pages of the introduction deal with the theories on the reception of (modern) art drawn up by the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (died 2002) and the museum curator Edward B. Henning (died 1993). However, in Van Wamel’s book the ideas of these two authors do not seem to play an important role, and it takes until chapter 11 before they are briefly mentioned again. Apparently, this boils down to little more than some academic trimmings.

Academic trimmings have completely disappeared from the rest of this dissertation. Using a very clear style of writing and with a lot of critical sense, Van Wamel analyzes the reception of Bosch’s art in the late fifteenth and in the sixteenth century. As was announed in the introduction, the various social groups are discussed one by one. Chapters 1-4 focus on the burghers. After an introductory chapter on the tradition of the bourgeois devotional portrait, chapter 2 deals with four works of Bosch in which the portraits of unknown patrons were once overpainted: the Ecce Homo panel from Frankfurt (with additional information on the copies), the St John the Baptist panel (Madrid), the Calvary panel (Brussels), and the St Wilgefortis triptych (Venice). Chapter 3 focuses on a number of works in which burghers can be identified through their portraits and/or coats of arms. These works are the Adoration of the Magi triptych in the Prado (with additional notice of some copies), the Ecce Homo triptych from Boston (produced by Bosch’s workshop), the Job triptych from Bruges (another workshop piece), and the copy of the Lisbon St Anthony’s interior panels from Berlin. In these chapters, the author more than once pays special attention to the clothes worn by some of the represented figures and to the wale of fabrics.

Chapter 5 deals with the ecclesiastical authorities, religious institutions, and clerics. The connection of most works discussed here with Bosch can only be derived from entries in chronicles and archival sources. These works were produced for the ’s-Hertogenbosch Church of St John, for the ’s-Hertogenbosch Fraternity of Our Lady, for the Dominican Order, for the Munster Church in Bonn (Germany), and for the Venetian Cardinal Domenico Grimani. There are also a number of works produced by followers of Bosch which have clerical devotional portraits: two wings with a Flagellation of Christ and a Carrying of the Cross (Philadelphia), the Crowning with Thorns panel (Antwerp), some versions of the Wedding at Cana, and the Jesus with the Pharisees panel (Castle Opocno).

The high nobility is the subject of chapters 6-11. This part of the book only uses the word ‘owners’, because in none of the cases it has been attested who were the commissioners of the works discussed here. These owners were mainly members of the Houses of Burgundy, Habsburg, and Trastámara, but also diplomats and advisers who were linked to their courts. Van Wamel’s study makes it very clear that most of these noble owners of Bosch works and their careers were very closely intertwined, so much so that one may readily speak of one or more networks within the early reception of Bosch’s art. In chapters 7 and 8 we read about: the counts of Nassau (Engelbrecht II / Henry III) and their relation to the Garden of Delights triptych,, Philip the Fair and courtier Hippolyte de Berthoz and their relation to the Vienna Last Judgement triptych and the Lisbon St Anthony triptych, the De Guevara family (in particular father Diego and son Felipe) and their relation to the Haywain triptych. Chapter 9 sums up the early owners of Bosch works that have been lost: Margareth of Austria, Mencía de Mendoza, the Van Bronckhorst-Van Boshuysen family, and Damião de Goís. Chapter 10 focuses on works which are attributed to Bosch in inventories of the possessions of noble persons, without us being able to check whether these attributions are correct today. Van Wamel notes: ‘The attribution of paintings to artists by means of inventories is a tricky affair’ [p. 252]. In this chapter we read about Isabella of Castile, Philips of Burgundy-Blatôn, the Van Croÿ family, and Juan Manuel (one of Philip the Fair’s advisers). Chapter 12 rounds off the book with some concluding observations.

-oOo-

Opdrachtgevers en vroege eigenaren van het werk van Jheronimus Bosch (Patrons and early owners of the art of Jheronimus Bosch) is a very praiseworthy book, which is not aiming at the general reader but will be read by most Bosch students with pleasure and attention. Definitely meeting up with a high academic standard, Van Wamel has read through an impressive amount of secondary literature, which resulted in a very handy and welcome survey of what we know or think we know today about the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century reception of the art of Bosch. The biographies of noble Bosch owners and enthusiasts in the third part of the book, for example, are outstanding and bring us closer to the world of Bosch than many other publications on the painter.

Deserving praise is also the fact that Van Wamel does not hesitate to critically comment on other authors, when necessary. On Stefan Fischer’s social positioning of the portrayed patron in the Brussels Calvary, for example [p. 70]. On Hannele Klemmetilä, who incorrectly states that only executioners wore striped clothing in the Middle Ages [p. 71]. On Paul Vandenbroeck, whose claim that Peter Col was tortured by the Duke of Alba because he did not want to reveal the hiding place of the Garden of Delights in the Brussels palace of William of Orange, is questioned by Van Wamel, and rightly so it seems [p. 188]. Even her supervisor Jos Koldeweij does not escape her critical-objective eye, when doubt is thrown on his theory that the St John the Baptist and St John on Patmos panels were meant for the altarpiece of the Fraternity of Our Lady [pp. 64-65 / 162], or when we read on page 206 that ‘some authors’ positioning of Hippolyte de Berthoz as one of the major patrons of Bosch is incorrect, or at least incomplete’.

As far as the debit side of this dissertation is concerned, it could be mentioned that Van Wamel almost exclusively falls back upon existing secondary literature and not on personal archival research for example (even though the way in which this secondary literature has been collected and adopted is admirable). Furthermore, when it comes down to final conclusions (relating to the closer identification of patrons, the original function of some paintings, or the precise role of early owners), we often read ‘maybe’, ‘possibly’, ‘it is probable’, and ‘it is not unlikely’, but this is something to which every reader of books on Bosch has long been accustomed. Other points of criticism are nothing but small faultfindings. On page 48, for example, Pontius Pilate with his judge’s staff in the Frankfurt Ecce Homo is incorrectly called an ‘executioner with stick’ (beul met roede), although on page 54 this same figure is correclty referred to as Pontius Pilate. And when we read on page 225 that the iconography of the Haywain ‘has been thoroughly analyzed in many publications’, whereas the accompanying endnote does refer to Vandenbroeck 2002 but not to De Bruyn 2001a (a dissertation dealing with precisely this topic), this seems – said in all (false?) modesty – a bit strange.

Unfortunate, though, and not exactly small faultfindings, are the typing errors, incorrect grammar, and not-corrected textual inaccuracies, which (admittedly) do not appear on every page but do show up constantly throughout the book, something one does not expect when dealing with a doctoral dissertation. Nevertheless, and in spite of these flaws, no one who wishes to write or speak about the early reception of the art of Bosch in the future will be able to ignore Van Wamel’s study.

[explicit 20 April 2022]