Vermet 2001

“Jheronimus Bosch: schilder, atelier of stijl?” (Bernard Vermet) 2001

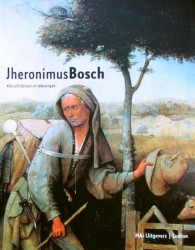

[in: Jos Koldeweij, Paul Vandenbroeck and Bernard Vermet [exhibition catalogue], Jheronimus Bosch – Alle schilderijen en tekeningen. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen – NAi Uitgevers – Ludion, Rotterdam-Ghent-Amsterdam, 2001, pp. 84-99]

Attribution and dating are two important issues of Bosch’s oeuvre. Although since Unverfehrt (1980) a consensus seems to have been reached about the authenticity of some 25 to 30 works, a lot of problems still remain. Technical means that can help in this matter are X-ray photography, infrared photography, infrared reflectography, the study of pigments and dendrochronology. Although the use of dendrochronology is limited and it can only offer a terminus post quem for a given panel, Vermet reconsiders the works attributed to Bosch by means of the dendrochronological research executed by professor Peter Klein (Hamburg). Page 88 offers the reader a survey of all the studied panels with their terminus post quem (the earliest year in which the panel may have been painted). Next Vermet draws a number of conclusions.

The first conclusion: the Escorial Crowning with Thorns, the Rotterdam Wedding at Cana, the Cologne Birth of Christ and the Philadelphia Ecce Homo triptych cannot be original Bosch panels because their wood can only have been used for painting after Bosch died (in 1516). The Prado Haywain is problematic: the wood can only have been painted after 1510-1516, but the numerous pentimenti point at an original composition. A second conclusion: the Rotterdam Pedlar was once the exterior of a triptych with the Paris Ship of Fools and the New Haven Allegory of Gluttony on the left interior wing and the Washington Death of a Miser on the right interior wing. The wood of these four panels seems to have come from the same tree and can have been painted from 1485 (Ship of Fools), 1487 (Pedlar) and 1488 (Death of a Miser) on.

These varying years should be understood as resulting from the flaws of the dendrochronological method. The question rises: why should the fact that the boards of these panels come from the same tree necessarily mean that they have once belonged to one triptych? Surely painters could create different and mutually independent paintings by using wood from one and the same tree? It is remarkable, though, that in 1972 Filedt Kok already noted that the underdrawings of these four paintings show many striking similarities.

Based on Klein’s dendrochronological research (the wood can have been painted from 1460-66 on) and on a stylistic analysis of the landscape Vermet here presents his hypothesis that the Garden of Delights is an early work (around 1480?) for the first time. According to Vermet there is a close stylistic affinity between the Garden of Delights and the Vienna Last Judgment. As in his opinion this latter triptych is the work that was commissioned by Philip the Fair in 1504, the Garden of Delights should also be placed around 1504 and so its early dating is problematic. Nevertheless the major part of the Bosch works that are considered authentic can have been painted (a long time) before 1500 and this could be a signal that Bosch had already reached a very high level of perfection at an early time (which would not have been exceptional).

The Frankfurt Ecce Homo panel is the only potential youthful Bosch work remaining. The dating of the wood points out that the Philadephia Adoration of the Magi and the St. Germain-en-Laye Conjuror cannot be youthful works. Probably they have to be attributed to Bosch’s workshop. The Madrid Cutting of the Stone is also a later work and perhaps partially a workshop product. Some of the costumes in the Madrid Seven Deadly Sins panel date from around 1500. Maybe it was executed by the Bosch discipulo mentioned by Guevara. The Madrid St. Anthony is too divergent from other Bosch originals.

It must have been a common practice in the Van Aken workshop that unequal masters collaborated in an equal way. The New York Adoration of the Magi may be a proof of this. The Madrid Adoration of the Magi, a work that could not be dated by means of dendrochronology yet, was probably painted in the eighties of the fifteenth century. The Brussels Crucifixion perhaps even somewhat earlier.

The Madrid St. John the Baptist and the Berlin St. John on Patmos may have been the exterior wings of the altarpiece of the Brotherhood of Our Lady, which was commissioned in 1488/89 (see Koldeweij 2001a). The weak spot of this hypothesis is the dating of the St. John on Patmos (its wood can have been painted from 1489-95 on): this dating fits but only in a very cramped way.

The core of the works that can be attributed to Bosch comprises the Madrid Adoration of the Magi, the Venice Hermits triptych, the Berlin St. John on Patmos, the Rotterdam St. Christopher, the Venice Crucified Female Martyr triptych, the Lisbon St. Anthony triptych and probably also the Madrid Haywain. All these works are signed, can be dated approximately around 1500 and share a number of stylistic features. To this can be added a number of works that have probably lost their signature: the triptych with the Rotterdam Pedlar, the Rotterdam Flood panels, the Vienna Carrying of the Cross and the Venice Visions from the Hereafter. The Ghent St. Hieronymus panel also belongs to this group, and (probably) also the Bruges Last Judgment triptych.

Gielis Panhedel van den Bossche (ca. 1490 – after 1545) was probably a painter related to Bosch’s workshop. A number of works that are very close to Bosch and yet don’t seem to be originals (because of dendrochronological dating or because of style) signal that Bosch did indeed have a workshop. Further research will have to find out more details about the chronology of the Bosch oeuvre and about the hands that have executed the paintings. Then again: is it really important to keep looking for those different hands: the Bosch workshop was a collective enterprise with several masters (members of Bosch’s family and assistants) and with (at least) one genius.

The major elements from Vermet’s argument (based on dendrochronology and stylistic analysis) are the fact that some works can no longer be considered Bosch originals (especially the Escorial Crowning with Thorns and the Rotterdam Wedding at Cana) and the emphasis on the existence of a Bosch workshop. For the rest Vermet’s conclusions use the words ‘perhaps’ and ‘probably’ a bit too often in order to be really convincing.

[explicit]