García Rodríguez 2018

“El Jardin de las delicias, Sigüenza y Platón” (Fernando García Rodríguez) 2018

[in: La Ciudad de Dios – Revista Agustiniana, vol. CCXXXI, nr. 2 (May-August 2018), pp. 365-398]

García Rodríguez (professor emeritus of the Complutense University in Madrid) argues that the key for a better understanding of the Garden of Delights triptych can not only be found in the Bible but also in ancient Greek myths and in particular in Plato’s Symposion. This thesis is based on the statement of fray José de Sigüenza (librarian of the Escorial) dating from 1605 that the owl, omnipresent in the art of Bosch, is a nocturnal bird dedicated to Minerva and to study, and a symbol of the people of Athens, where philosophy flourished. A piece of art necesita de una interpretación de acuerdo con los supuestos culturales que la han sustentado (needs an interpretation in accordance with the cultural premises from which it arose). That is why the author gives a number of examples showing that Plato’s philosophy was still known and appeciated around 1500 [pp. 379-380].

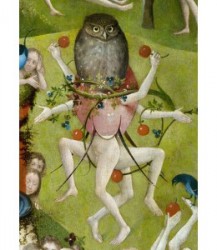

The exterior panels of the Garden of Delights are dominated by divine Love creating the world. The interior panels show the triumph of Eros (Amor) and of Beauty. Christ, who brings together Adam and Eve in the left interior panel, represents Amor (divine Love). As opposed to what many authors claim, no disturbing sinfulness can be seen in this left interior panel. The panel is dominated by Love uniting man and woman. The owl (in the fountain) occupies a central position as a symbol of Athena, the goddess of wisdom and of reason controlling Love.

The central panel with its numerous nudes represents the triumph of Love, in particular of the celestial goddess Afrodita Urania, whom we know from Plato’s Symposion. There is nothing sinful about the carousel of riders turning around a pond with naked women. These riders are sitting on animals, and thus they are placed above their lower desires. What we see here is all exalted courtly love with no sign of trivial carnal lust (Afrodita Pandema in the Symposion). Here, love is passion resulting from the observation of beauty. When Bruegel paints dancing peasants, he represents the lower desires of rustic man, governed by Dionysos. Bosch deals with love governed by reason and wit and this love is Apollonian and platonic.

This regulating wit is symbolised by the owl. Not only in the The field has eyes, the wood has ears drawing (Berlin), but also in the detail of the Garden’s central panel with two dancing figures inside a fruit skin and an owl on top of it (lower right). García Rodríguez interprets these dancers as one single figure with four arms and legs and argues that here Bosch was inspired by the androgyne sex described in the Symposion: apart from men and women there were originally also creatures that belonged to both sexes at the same time. The figure from whose behind flowers are appearing could refer to la educación sexual en Grecia (with this the author is apparently referring to the ancient Greek men’s predilection for the love of boys).

The author pays very little attention to the right interior panel (according to him ‘one of the most infernal’ hells that Bosch ever painted). In this hell the lower passions are punished, see for example the ‘knight’ who is being devoured by animals looking like basilisks (aren’t these just dogs?), in other words by his own lower passions.

The approach to Bosch suggested in this article does not sound very convincing. The thesis that Bosch was inspired by Plato is not made plausible and is contradicted by Bosch’s oeuvre at large. The author largely ignores this oeuvre, focuses on the Garden of Delights again ignoring a whole range of details and just choosing what fits (or rather seems to fit) his argument. Moreover, most Bosch experts will agree that Sigüenza’s statement about the owl in the art of Bosch is not the most fortunate part of his otherwise interesting comment. García Rodríguez’ article thus seems to be another example of ‘gesol met Jeroen Bosch’ (Bosch mumbo jumbo). Unfortunately, the tone of the article is often extremely arrogant and aggressive towards other Bosch authors.

[explicit 23rd February 2019]