Gombrich 1969

“Bosch’s ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’: A Progress Report” (E.H. Gombrich) 1969

[in: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. XXXII (1969), pp. 162-170]

[Also mentioned in Gibson 1983: 90 (E102)]

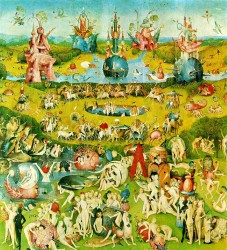

In this article Gombrich defends the thesis that the actual title of the Garden of Earthly Delights triptych should be Sicut erat in diebus Noe or The Lesson of the Flood. The closed wings do not depict the third day of creation but the earth immediately after the Flood. The central panel shows the earth before the Flood. Gombrich presents some thirteen arguments for this thesis.

1 The bright curved streaks on the left outer wing cannot be all reflections on one enclosing surface (more precisely on the surface of the crystal ball representing the firmament). These streaks must be interpreted as a rainbow. In the Bible the rainbow is the token of the covenant which God made with Noah after the Flood. In the left upper corner of the closed wings God is seen pointing at the pages of a book as if He were speaking of the covenant. The earth is still surrounded by receding waters.

2 The closed wings cannot represent the third day of creation because there are a number of castles and other buildings in the landscape.

3 The quotation from Psalm 33 at the top of the closed wings does not contradict the interpretation of the closed wings as an image of the earth after the Flood. The quotation itself (Ipse dixit et facta sunt, Ipse mandavit et creata sunt) refers to the punishment of the Flood, but the context of this quotation in the Psalm clearly signals that the Lord will protect the righteous. The rainbow is another signal that the good will not perish with the wicked.

4 If the closed wings represent the earth after the Flood, an obvious question is: where do we see the Ark of Noah? But all three panels of the triptych have been trimmed: this can be demonstrated through a comparison with the sixteenth-century tapestry based on them. Moreover the circle of the flat earth is bisected by a double frame which may not be the original. A central strip about one-sixth of the total widths (about 32 cm out of a total width of some 194 cm) would then have become invisible. On this strip the Ark may be (have been) painted.

5 If the closed wings show the earth after the Flood, the central panel may well represent the earth before the Flood. The Biblical report on the Flood remains vague and superficial. It is remarkable that only in Genesis 6: 13 God says that He will destroy mankind ànd the earth: this created an exegetical problem because God did destroy mankind but not the earth. The medieval commentaries on the Bible (from the ninth-century Glossa Ordinaria tot Peter Comestor’s twelfth-century Historia Scholastica) explain that God meant that He would destroy the earth’s fertility. Bosch has represented the unusual fertility of antediluvian life by means of gigantic birds and fruits. The medieval commentaries on the Bible also mention that people were vegetarians before the Flood. After the Flood, when earth was far less fertile, God allowed mankind to eat meat (see Genesis 9: 3).

6 Early mankind’s vegetarianism is the reason why in the central panel wild animals don’t seem to fear man. But there is also a linguistic aspect to the presence of these animals: mankind has sunk to the level of beasts.

7 Traditionally the medieval comments on the Bible pointed out Lust as the cause of the Flood because Lust had driven man to madness. See the Biblical account about the ‘sons of God’ who had sexual intercourse with the ‘daughters of man’. The winged figures in the right-hand upper corner of the central panel may be these ‘sons of God’.

8 More often, though, for example by St. Augustine, the ‘sons of God’ are identified as the offspring of Seth (Noah’s ancestor and a good man) and the ‘daughters of man’ as women from Cain’s tribe. In the Middle Ages it was believed that the offspring of Cain were black people (the black colour of their skin being the ‘Mark of Cain’). Which would explain the numerous black people in the central panel.

9 The inventory of the purchases of Archduke Ernest at Brussels shows that a triptych by Bosch was bought for his collection in 1595: ‘A history with naked people, sicut erat in diebus Noe’. It was suggested earlier that this item was the same as the painting described in the inventory of the Prague Kunst und Schatzkammer of 1621 under the title ‘the unchaste life before the Flood’. In the 1621 inventory this item is followed by ‘two altar wings how the world was created’. Undoubtedly this was a copy or a replica of the Garden of Earthly Delights, which should actually be called Sicut erat in diebus Noe.

10 ‘Sicut erat in diebus Noe’ is a quotation from the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 24: 36-39). In this text Christ is referring to the fact that mankind is not preparing itself for the Day of Judgement and compares it to mankind before the Flood which was also unconcerned about its future. As a result Bosch focuses on the unconcern, the absence of a sense of sin of mankind before the Flood, rather than on its wickedness. He who doesn’t grasp this, is easily inclined to interpret the central panel in a positive way.

11 There exists a Dutch Renaissance engraving by Sadeler after Barendzoon with the title Sicut autem erat in diebus Noe: naked people are feasting in a landscape. But they are eating fowl so they are not vegetarians. What this engraving does prove, is that the subject of Bosch’s central panel was not unique: it conforms well to the tradition of Biblical illustration and it follows that in order to explain Bosch’s paintings scholars should more often consult the Bible and comments on the Bible.

12 The presence of glass implements many of which look like test-tubes raises the question: was chemistry practised by the antediluvians? Several medieval sources confirm that mankind practised science on a high level before the Flood. The Jewish writer Josephus mentions that the ‘children of Seth’ wrote all their wisdom on two pillars. These pillars were made of hard material and were meant to survive the Flood for the ‘children of Seth’ knew that Adam had predicted the destruction of the world. In a chronicle by Rudolf von Ems we read that the two pillars were made by sinful mankind before the Flood which was trying to find a material ‘harder than glass’. There is something very much like a pillar in the bottom right-hand corner of the central panel. The pointing man behind it, the only dressed figure in the panel, might be Noah.

13 The left inner wing already signals that God regrets His creation: corruption is already present in Eden. As is shown by the animals creeping from a pond, the giant trees with the portentous black swarms of birds and the flesh colour of the fountain. This last detail can be compared to a passage from St. Ambrosius’ Liber de Noe et Arca: ‘It is out of the flesh that the rivers of concupiscence and other evils burst forth as from a fountain’.

In many ways this is a brilliant article which fulfills a key role in the iconographic analysis of the Garden of Earthly Delights but after 1969 some Bosch scholars have not given it the attention it deserves. One of the reasons for this is no doubt that Gombrich’s first four arguments have been proven untenable. The bright streaks do not represent a rainbow, no buildings can be seen in the landschape on the closed wings and that the Ark has become invisible because of the trimming of the panels does not sound very convincing. Gombrich’s interpretation of the closed wings as a depiction of ‘the earth after the Flood’ can duly be discarded. All the same, his interpretation of the inner panels, and especially that of the central panel, is ingenious in many respects. Too easily some writers on Bosch dispense with arguments 5-13 because arguments 1-4 turn out to be terribly weak. Another case of throwing away the baby with the bath water.

[explicit 25th December 2013]