Grauls 1938

“Taalkundige toelichting bij het hooi en den hooiwagen” (Jan Grauls) 1938

[in: Gentsche Bijdragen tot de Kunstgeschiedenis, V (1938), pp. 156-177]

[Also mentioned in Gibson 1983: 98 (E150)]

The Middle Dutch word hooi means: dry grass, but also: grass which is in the field and is ready to be mown. This word was used in Middle Dutch to translate the famous sentence omnis caro foenum (all flesh is hay) from Jesaiah. Grauls points out a number of Middle Dutch sayings with hay from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: niet een hooi (not a hay = not at all, nothing), een/iemands kaproen met hooi vullen (to fill someone’s cap with hay = to cheat, to fool, to flatter someone), het is al hooi (it is all hay = everything is lost, it is all worth nothing) and om het lange hooi plukken (to pick the long hay = to be greedy, to try to get as much as possible). In these idioms hay had a negative meaning. In the French language foin had a similar negative meaning. Grauls also points out the expression de hooiwagen drijven (met iemand) (to drive the haywain with someone), meaning: to mock someone, to cheat someone. In this idiom the word ‘haywain’ also has a pejorative meaning.

Grauls further analyses the Middle Dutch texts which accompany the etchings Al Hoy made by Bartholomeus de Mompere (1559) and J. Horenbault (1608). In these etchings a whole series of vices and sins are associated with hay in a metaphorical way. The notion ‘hay’ had a lot more negative connotations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries than can be derived from our dictionaries. Grauls also analyses the Middle Dutch and French captions in the engraving Den Dans des Werelts (The Dance of the World). The hay and the smoke in these captions (both referring to the vanity of earthly matters) are depicted in the engraving by means of a bundle of hay with the word vanitas written on it, and of a burning torch.

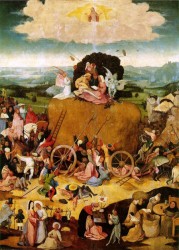

Being fond of the popular language Bosch will certainly have known these idioms with hay. But which of these idioms did he actually depict? Grauls does not believe that one particular idiom can be identified as the basic idea of the central panel of the Haywain triptych. Jesaiah’s words all flesh is hay, which are often mentioned in this context, were probably not commonly used in the popular language around 1500 and the proverb suggested by Tolnay (the world is a haystack and everyone tries to pick from it as much as possible) has only been documented since 1823. We do know a similar saying from 1727: he who is standing next to the haystack, picks from it. But why should we be looking in the Bible and in modern language, if we can point out with certainty half a dozen sayings and proverbs which belong to Bosch’s own times? Grauls is convinced that all the scenes in Bosch’s painting can be linked to an expression or a proverb about hay and that the idioms he has mentioned, are all good candidates. What the persons on the central panel are doing, it is all hay, the group around the haywain is picking the long hay (is looking for its own profit) and the devils to the right are driving the haywain with (are cheating) greedy mankind.

With all due respect for the obvious merits of this article, two objections against Graul’s view can be uttered. First: it is not because the biblical saying ‘all flesh is hay’ was not common in the popular language, that Bosch did not depict it. Bosch made use of the popular language more than once, but certainly not always. Compare for instance the quotation from the Psalms on the closed wings of the Garden of Delights triptych and the quotation from Deuteronomy on the Prado Seven Deadly Sins panel.

Second. It is by no means certain that the biblical saying ‘all flesh is hay’ was relatively unknown with the common people. In late-medieval texts the expression is quoted so many times that it must have been a very well-known scriptural passage. Even illiterates could frequently come in touch with it by listening to sermons. This second objection is also signalled by Paul Vandenbroeck [Vandenbroeck 1987c: 123]: ‘It is clear that this Old Testament view on “hay” was well-known in the Netherlands during the 15th and 16th centuries, as will be shown by the following (which refutes the view of Grauls 1938, p. 173)’.

[explicit]