Harbison 1976

The Last Judgment in Sixteenth Century Northern Europe: A Study of the Relation Between Art and the Reformation (Craig Harbison) 1976

[Outstanding Dissertations in the Fine Arts, Garland, New York-London, 1976, pp. 69-83 / 197-202]

[Also mentioned in Gibson 1983: 185 (J10)]

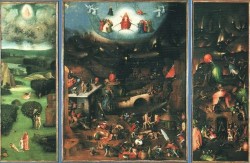

It is not Harbison’s intention to offer a survey of Bosch’s symbolism, he only wants to analyse Bosch’s ‘millenarian thought’. Although it is uncertain whether the Prado Seven Deadly Sins panel is an authentic work, Harbison considers the tondo in the upper right corner to be Bosch’s oldest depiction of the Last Judgment. Here Bosch stays very close to the tradition. The majority of Bosch scholars believe, as does Harbison himself, that the Vienna Last Judgment triptych is an authentic work by the master. Although on the central panel a small number of saved souls can be seen, Bosch’s view on mankind is mainly pessimistic here: most men are sinners, hardly aware of God’s judgment.

In Bosch’s later representations of the Last Judgment this pessimism has become milder. In the Bruges Last Judgment triptych (here considered to be an authentic work) Bosch shows the way to heaven on the left wing, but on the central panel the presence of evil and sin is overwhelming and the judging Christ is situated at the top, far away from the turmoil beneath Him. Another Last Judgment triptych, only preserved through a copy (formerly in Ghent, Maeterlinck Collection) and some fragments, shows affinities with this work: on the left wing the way to heaven, on the right wing a hell and on the central panel sinful mankind.

In an engraving with the Last Judgment by Allaert du Hameel (after a design by Bosch) the struggle between good and evil forces for the human soul is depicted for the first time. The same is the case on a Last Judgment panel (London, private property) which is probably a copy of a lost original. According to Harbison all this leads to a lost triptych, only preserved through a Last Judgment print edited by Hieronymus Cock, which represents the final stage of Bosch’s eschatological view. The print depicts a triptych, with heaven to the left, hell to the right and in the middle a Last Judgment without a divine judge. Apparently here Bosch has been influenced by his humanist contemporaries, laying more emphasis on man’s choice between good and evil than on the sinful character of mankind. Bosch thus shows affinity with the humanist ideals of the higher circles in the Netherlands (to which his patrons belonged) and can be seen as a precursor of the Reformation.

It will be obvious that Harbison’s interpretation of the evolution in Bosch’s treatment of the Last Judgment theme is based on weak arguments. The authenticity and the dating of the works he analyses, are very problematical, making it risky to draw any conclusions. The work in which Harbison wishes to see the culmination of Bosch’s view, has only come down to us through a print from the middle of the sixteenth century. Bosch’s supposed affinity with the humanists becomes less evident when in the next paragraph Harbison writes about Erasmus…

In the past the Dutch humanist Erasmus has more than once been linked to the work of Bosch. But Bosch wanted to enchant his public with phantastic depictions of infernal pain and tortures, whereas Erasmus shied away from all fanaticism and anxious excitement. He wanted to approach death in a calm way. In his earliest works, such as The Praise of Folly, he wrote in a negative way about detailed descriptions of hell and eschatological thirst for sensation. For him it was more important to meditate quietly about the eventual spiritual rebirth of mankind.

Bosch’s apocalyptic imagery often influenced artists from the later sixteenth century. A good example of this is the way in which he depicts the ascent of souls to heaven on one of the four panels that are now in Venice. Quite a number of Bosch’s followers made pastiches after his work, resulting in Boschian compositions without much coherence. The painter of the Munich Last Judgment fragment was probably someone who could dispose of Bosch’s original workshop drawings. Painters such as Jan Mandijn and Peter Huys show more creative talent when dealing with Bosch’s diabolical imagery, but are obviously more appealed by Bosch’s lighter, extravagant side (his devils and his infernal motifs) than by the profounder aspects of his world view. The only true heir of Bosch in the sixteenth century was of course Peter Bruegel: he succeeded in producing an original restatement of the master’s oeuvre.

[explicit]