Koerner 2016

Bosch & Bruegel – From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life (Joseph Leo Koerner) 2016

[Bollingen Series XXXV: Volume 57, Princeton University Press-The A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts (National Gallery of Art) , Princeton-Oxford-Washington, 2016, 414 pages]

Joseph Leo Koerner is a Professor of Art History at Harvard University. His book Bosch & Bruegel, published in 2016 by Princeton University Press, presents a revised version of the talks which he delivered as part of the A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts at the National Gallery of Art (Washington) in 2007. According to the Preface, the book’s purpose is: ‘To communicate to a general public the achievements of two great painters of everyday life. Non-experts are an ideal audience for this, since with everyday life everyone is an expert. I have tried to meet works of art as one meets things in life: contingently, in the flow of experience’ [p. X]. The text, blesssed with a sumptuous design and an attractive layout thanks to the publishers, is divided in three parts, comprising eleven chapters. Chapters 1 to 4 introduce the ‘parallel worlds’ of Bosch and Bruegel, after which chapters 5-8 (Part I) and chapters 9-11 (Part II) deal with Bosch and Bruegel, respectively.

Bosch & Bruegel is not your common scholarly treatise. In fact, it is a collection of interlinked essays, written in an extremely polished, sophisticated style (the book won the Prose Award for Art and Art Criticism in 2017) and presenting to the reader a broad, impressionistic, learned, intelligent, often somewhat highbrow view on Bosch and Bruegel, in which art history tends to blend with art philosophy, anthropology, and observations on modern society (the pages 151-153, for example, deal with two movies, The Truman Show and The Matrix). As a result, this publication seems to meet with the highest academic standards, at least at first sight, and – in spite of its fluent style and partially due to numerous elaborations and excurses – requires a high level of concentration and even stamina from the reader. To such an extent, that one may wonder whether ‘non-experts are an ideal audience for this’.

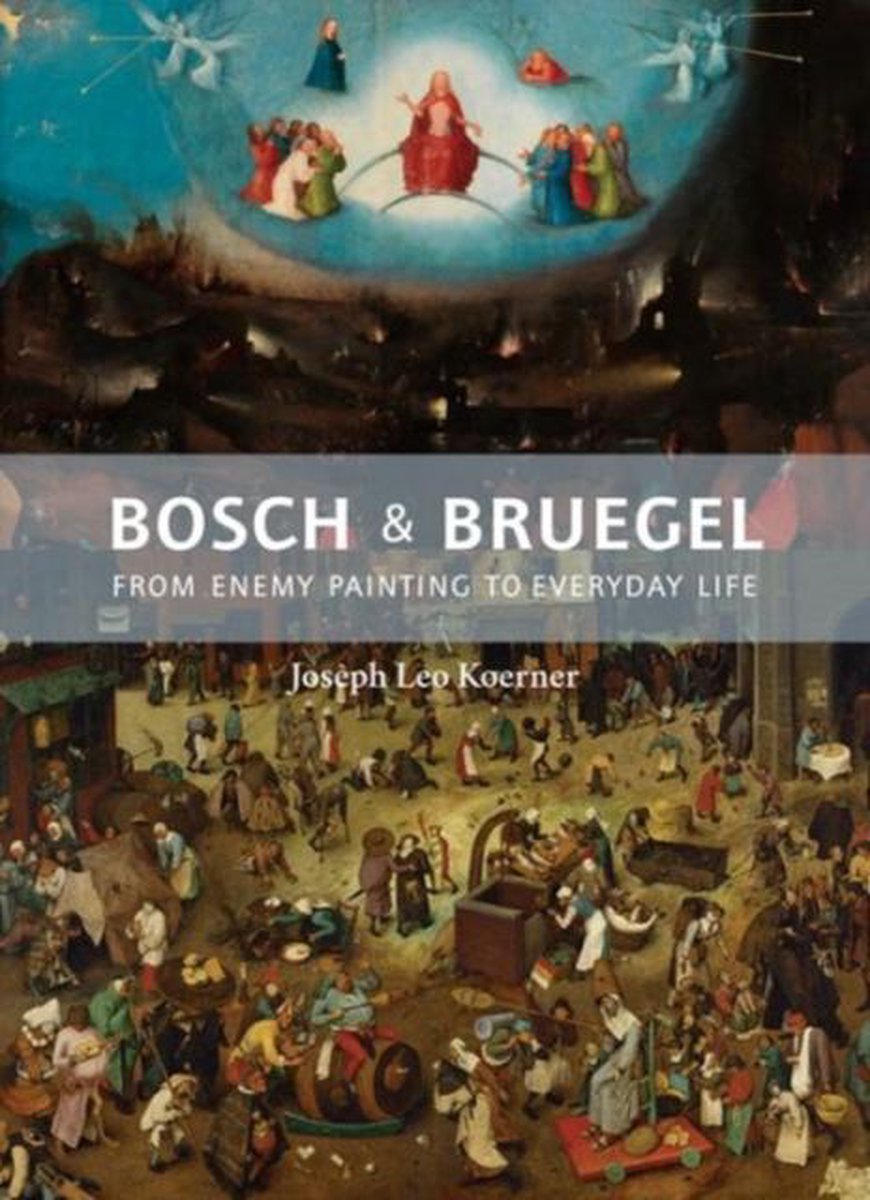

The general purport of Koerner’s argument can be summarized as follows. Whereas Bosch produced religious paintings dominated by a medieval approach of the world, in which God is the wrathful spectator of sinful mankind, Bruegel belongs to the Renaissance and paints a more secular view of the world, in which there is still anger, pain, and deception but from which God is largely detached. With Bosch, scenes from everyday life are embedded in a context referring to the corruption of mankind and its hostile alienation from God. With Bruegel everyday life has become the main subject, resulting in what we call ‘genre painting’ today. In Koerner’s own words: ‘I have tried to place Bosch and Bruegel side by side, illuminating the one through his proximity to, and difference from, the other. But I also make an argument about artistic genealogy: how the history of art passed from Bosch to Bruegel, and – further – how a new form of painting devoted to ordinary life could begin with something altogether unordinary: a metaphysical struggle, waged through the medium of painted images, against the Old Enemy, Satan’ [p. 92]. That is why the upper part of the cover shows Christ at the Last Judgement (from Bosch’s Vienna triptych), whereas the lower part is a detail from Bruegel’s Battle Between Carnival and Lent (Vienna). ‘In Bosch’s world, the familiar is enemy territory, and those who befriend it are foes to God. However, brought down to earth and there portrayed as if “from life”, this cosmic hostility becomes the cradle of a painting of everyday life’ [pp. viii-ix].

In his review of Koerner’s book, Mitchell B. Merback writes: ‘How well Koerner’s interpretations will stand up to the scrutiny of Bosch and Bruegel’s scholarly partisans is another matter, and one that remains beyond the scope of this essay’. Matthijs Ilsink is definitely a scholarly partisan of Bosch and Bruegel, and he published an (in my opinion) excellent review in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte. Ilsink notes:

"The essence (and value) of the book cannot be described by stripping the argument to the bone. The embellishment of the argument, the way that it is presented, forms part of the argument itself. As he says himself, the author’s subjective individual experience plays an important role in his readings of the art of Bosch and Bruegel. The account of that experience is full of artifice and elegance, and sometimes pomp. To summarize that experience in words other than the author’s is extremely difficult. On the one hand, this credits the singular character of the auteur. On the other hand, this complicates critical discourse with colleagues. It is difficult to disagree with someone’s experiences. At a certain point, one can only share them. Reading this book, reading it slowly, is an experience both pleasant and educational. Reading it slowly, however, also brings to the fore the sometimes casual causal argumentation. At certain points one feels that in order to make his point or to illustrate the point made, the author stretches the facts somewhat."

-oOo-

Not being a Bruegel specialist, I will further limit myself to two general remarks about Koerner’s approach to Bosch (one regarding style, the other regarding content), after which I will have a closer look at chapters 6 and 7/8, which deal with the Lisbon St Anthony triptych and the Prado Garden of Delights triptych. Everyone who has read Koerner’s book will agree that the author is extremely eloquent. Melion, in another review, calls the book ‘fluently written’, Merback considers the author an ‘exceptional prose stylist’, and Ilsink notes: ‘The text expresses an enormous enthusiasm for looking at art and, perhaps even more so, writing about it’. All of this is true, and yet every now and then what Koerner writes leans towards what in English is called purple prose. According to Wikipedia, purple prose ‘is prose text that is so extravagant, ornate, or flowery as to break the flow and draw excessive attention to itself’. In his review, Ilsink calls it ‘pomp’. Let me just give one example. On page 49, Koerner is writing about the Haywain triptych and about the peddler in its exterior panels:

"A thing that is nothing, hay is our flesh. Lusting after itself, flesh withers and vanishes. Hay also stands for Bosch’s painting: a wooden object of no consequence, mere fuel for hell’s consuming flames. Thus the peddler, with his thing-filled backpack made of straw, mutates into the humanity grasping at straws, which mutates into the viewer gazing at painted straw."

This almost sounds like poetic prose, it is a nice train of thought, it makes a scholarly and learned impression, but does it bring us any closer to the actual scenes that were painted by Bosch? Obviously, whether it is ‘a joy’ to read passages such as these (and the book abounds with them), as Ilsink kindly pointed out, is up to every reader to decide for himself/herself.

A second general remark. ‘Enmity’ seems to be a key word in Koerner’s approach to Bosch (‘contingency’ is another one). ‘Bosch is the great master of Christian aggression’ [p. 111]. ‘Bosch was an expert in enmity. Hatred was his professional specialty’ [p. 133]. ‘Bosch pictures a world so structured by enmity that his own world pictures become hostile, as well’ [p. 362]. Although it cannot be denied that Bosch is partial to depicting man’s sins and folly, I sincerely believe that Koerner is pushing his argument too far by overstressing the ‘enmity’ aspect of Bosch’s paintings. A good example is what he writes about the Haywain: ‘At the head of the parade, monstrous demons, uncontested, lead humanity into their trap. And joining this ambush is God himself, who, facing universal hostility despite having come as a friend and preaching love, unleashes his wrath in hell’ [p. 67]. And on page 359: ‘In Bosch, God alone answers the question of human things, and his answer is war on them’. When Koerner writes things like these, he is not writing about the Bosch that I know. Koerner’s God reminds me of the Old Testament God: wrathful, merciless, easily provoked, always keen on revenge. ‘Where does all this enmity come from?’ Koerner asks on page 145. It is a good question, which could also be asked to Koerner himself. The answer may be related to Koerner’s Jewish background and his experiences as a young boy in Vienna during the Second World War (about which he writes in the Preface), but that is beyond the scope of this review. What matters here, is that in my opinion Bosch was far less pessimistic and misanthropic than Koerner wants us to believe.

The art of Bosch is basically didactic and moralizing, and the Haywain triptych is a painted sermon. It does not represent a reality but a virtual reality, at the same time warning of a potential ill-fated future (eternal punishment in Hell) and showing how to avoid that ill fate. In the upper centre panel we do not see a merciless God the Father who ‘unleashes his wrath in hell’, but a merciful God the Son, Jesus Christ, who is showing His wounds to remind the viewer that thanks to His death at the Cross every man can be saved and reach Heaven, on the condition that he avoids sin or – if he has already sinned – shows remorse. As I have argued elsewhere, the peddler in the exterior panels, keeping an aggressive diabolical dog at a distance with a stick, is an example of such a repentant sinner (the exterior panels of Bosch’s triptychs always show a good example). This is why I concur with Gary Schwartz, who published an interesting essay in a 2016 exhibition catalogue [Gary Schwartz, “Eine Welt ohne Sünde – Hieronymus Bosch als Visionär”, in: Michael Philipp (ed.), Verkehrte Welt – Das Jahrhundert von Hieronymus Bosch. Exhibition catalogue (Hamburg, Bucerius Kunst Forum, 4th June – 11th September 2016), Hamburg-München, 2016, pp. 8-17]. In this essay Schwartz compares the art of Bosch to the Vision of Tondal (written by a Brother Marcus), a text that more than likely was known to Bosch and inspired him. Schwartz notes (and I translate from the German):

"Brother Marcus and Hieronymus Bosch shared the intention to startle their fellow-man with their creative forces and to make them repent, and thus they tried to save him from Hell. (…) The more an artist or author is capable of representing the tortures of Hell, the more he contributes to the reader’s or viewer’s salvation." [pp. 11 / 12]

Neither Bosch nor the God that he depicts are ‘waging war’ on man. On the contrary: when Bosch paints the sins of mankind and their punishment in Hell, his goal is to show to his viewers the bad example, the potential consequences of that bad example, and the way to avoid those consequences. In simple English the message is: if you do not want to undergo terrible tortures in Hell, stay away from sin, and you will be saved. Exactly the same moralistic ‘trick’ can be found in late medieval edifying treatises which – just like Bosch – describe the infernal punishments in detail, such as for example the fifteenth-century Boeck vander Voirsienicheit Godes (The Book of God’s Providence). In his introduction the anonymous author writes (and I translate from the Middle Dutch):

"Because man is weak and prepared to sin, and because the fierce devils and the unreliable world constantly try to make mankind sin, I have written a little about the eternal pains and about the eternal life. But in many places in an allegorical way. So that the fear of the horrible pains will make him give up sin and protect him from further sins."

Koerner’s obsession with ‘enmity’ and ‘aggression’ in the art of Bosch leads to highly debatable interpretations when he writes about other paintings as well, often unnecessarily complicating things that are in fact quite simple. Two good examples of this can be found in Koerner’s analysis of the Prado Epiphany. On page 127 he writes about the three armies in the background of the centre panel: ‘Dressing the troops in Turkish and Mongol gear, Bosch portrays geopolitical enemies contending for Jerusalem but poised to turn their wrath on Europe’. But are these three armies not merely the trains of the three Magi on their way to meet each other, and does the ‘Turkish and Mongol gear’ not simply refer to the fact that they came from the East? Even the gifts presented to the Christ Child by the Magi do not escape Koerner’s mistrust. He writes:

"From the moment of his birth in Bethlehem, it seems, the world’s response to Christ will indeed be hostile. The first gift, the eldest Magus’s statuette, predicts this outcome by showing Abraham sacrificing his son at God’s inscrutable demand. An angel suspends the blow, but in the death that the old story foreshadows, God gives to the enemies his own son to be murdered. Death is the only peacemaking gift." [p. 129]

And on page 150 he adds: ‘In their strange facture and symbolism, the gifts of the Magi typify Bosch’s art. Were we to know why the artist gave the first Magus’s gift frogs for feet, we would understand much about his deepest intentions’. This interpretation is far too morbid. It is of course true that in the Middle Ages Abraham’s sacrificing his own son Isaac was seen as a prototype of Christ’s Crucifixion, but was (and is) this sacrifice of Christ not the reason why every sinner could (and can) hope for salvation? And what if the frogs are toads and refer to evil and to the devil, as they so often do with Bosch and with other artists and writers around 1500? If you put two and two together, does the fact that the Magus’s gift crushes the toads not simply mean that thanks to Christ’s death at the cross evil can be overcome? According to this interpretation, death is indeed a ‘peacemaking gift’ and not an act of war.

-oOo-

In chapter 6 [pp. 151-178] Koerner focuses on the Lisbon St Anthony triptych. In the first half of the chapter he writes about its four primary scenes (i.e. the scenes in which Anthony appears) and about the exterior panels. In the centre of the centre panel Anthony points at Christ, who is also the protagonist in the exterior panels. In the left interior panel Anthony is beaten up by devils, after which the saint is carried to his hermitage, which has been changed into a brothel by the devils. That ‘both events (are) described by Athanasius’ [p. 159] is not completely correct, for Athanasius’s Vita Antonii does not mention that the devils lifted Anthony up into the sky. And the right interior panel shows the devil queen (known to Bosch via a translated Arab source). These pages have some nice observations, for example when Koerner writes about the tiny Christ figure in the centre panel that looking at Him ‘feels like peering through the wrong end of a telescope’ [p. 171]. And the complete triptych ‘is the most amazing spectacle of painted devilry in all of art. The saint’s ascetic withdrawal has enraged these demons. Wrathfully they attack Anthony with a plague of phantasms’ [p. 157].

These phantasms fill up the larger part of the interior panels (some 21 scenes), but Koerner hardly spends a word on them. Instead, the second half of the chapter offers the reader an elaboration on Bosch’s technique (with again a nice sentence: ‘Instead of illusions of reality, Bosch makes real-looking illusions’, p. 163) and another one on idolatry, starting from the golden calf and a monkey-idol represented on the column in the centre panel. Koerner points out that Anthony waged a war on heresy, idolatry, and false images but used an image himself: the sign of the cross. And yet, when Anthony was beaten up by the devils (see the Vita Antonii), Christ did not help him but only appeared to the saint aftwerwards. Because Christ wanted to teach Anthony humility, writes Koerner. After which the last paragraph focuses on two tricks used by Bosch to convey his message: Anthony is placed at the absolute, geometric centre of the triptych, and he looks at us, the viewers, thus involving us in the painting and encouraging us to think about where we stand. ‘But what would have happened if instead of putting a tiny escape hatch at the center, in the form of Anthony’s true look, Bosch had made the center the most dangerous place of all?’ [p. 178].

-oOo-

This last sentence announces Koerner’s discussion of the Garden of Delights triptych in chapter 7 [pp. 179-222]. The first section of this chapter offers an excellent introduction to the Garden’s problematic position within the Bosch oeuvre, and its key passage is (referring to what is going on in the centre panel): ‘Are these paradisiacal pleasures free of painful consequences? Or are they sinful, with hell as their reward? To this day, no one has resolved this most basic question’ [p. 183]. But it does not tell us anything that we did not know already or cannot read elsewhere.

The next section first focuses on the exterior panels. Bosch portrays the third day of Creation when God separated earth from water. It was sometimes held that in this division good and evil were also separated and that on that day Lucifer and his minions were thrust out of heaven, which is perhaps symbolized by the atmospheric turbulence above the newly formed land. Again, this is nothing new, but then the author elaborates on hyle (an ancient Greek term for primal matter), starting from Hartmann Schedel’s 1493 Book of Chronicles, and on St Augustine’s comment on the verse from Psalm 33, which we can see in the upper exterior panels. In my opinion, these excurses boil down to what Roger Marijnissen liked to call Gelehrtenquatsch, but perhaps they are too high for my wit. In the left interior panel Eve is presented to Adam, whose blushing cheeks point out his desire for her. If we follow Adam’s gaze, the vector runs from Eve’s face through the centre panel (filled with lustful activities) until it reaches the Tree-Man in the right interior panel. Koerner provides a photo of the Garden with a red straight line in it to illustrate this.

Stripped from all erudite verbosity, the third section of the seventh chapter argues that the Garden tells a story of desire. ‘Aroused in Adam before the Fall, desire traverses a humanity that, kept inhuman by animal drives, burns itself out in hell’ [p. 197]. The exterior panels and the carnivorous beasts in the left interior panel suggest that before the Fall something about nature may already have been corrupt. As is well-known to Bosch experts, every author concurs on the erotic nature of the Garden’s centre panel. The question which haunts the on-going debate is: are these erotic acts and symbols to be interpreted in a negative or positive way?Apparently, Koerner is going to argue in favour of the former. Noteworthy: the scene with three men around a bursting seedpod at the base of the centre panel is said to insinuate masturbatory practices. Straightforward interpretations of separate scenes in the centre panel such as these are quite rare in the literature about Bosch. In my opinion, they should never be discouraged.

After a rather woolly elaboration on the question of whether evil already existed before the Fall in section four, section five deals with the centre panel. And again, Koerner goes a step further than other authors before him when interpreting the scene in the ‘hole’ underneath the blue ball floating on the water:

"A man seems to penetrate a woman from the rear. His arm position suggests he is guiding his member into her right now. Meanwhile, dashing all hopes that the triptych celebrates marital vows, a second man fondles the woman’s genitals. His fingertips, with the hidden member of the other man, may now be reaching into the woman precisely below the water’s surface." [p. 208]

Koerner associates this ‘abject hole at the garden’s center’ with the structure of Earth in the triptych’s shutters and its similar low, watery horizon. He then points out the presence of numerous behinds (Koerner uses the word ‘asses’) in the centre panel and concludes that quite a number of its scenes can be associated with the vitium contra naturam, the sin against nature or sodomy, which in the Middle Ages referred to every sexual act that did not lead to procreation. Thus, the people in the centre panel are disobeying God’s command to ‘be fruitful and multiply’: ‘A sexually perverse and thoroughly heretical un-humanity rebels against creation itself’ [p. 215]. In my opinion, these pages [208-218] are very strong and show us Koerner at his best: as a keen observer and a clever interpreter, as soon as he dispenses with all redundant pomp.

Unfortunately, after having reiterated the unchaste purport of the scenes in the centre panel, in the sixth and last section of chapter seven Koerner again loses himself (and many readers, I assume) in yet another woolly elaboration, this time dealing with the colours of the centre panel, which fascinate us and cause us to behold the world through ‘idolatrous eyes’, culminating in the last sentences of the chapter: ‘Painter of enemies, Bosch shows what it looks like to see through idolatrous eyes. He makes me into the enemy, into my own enemy’ [p. 222]. By which the author means (I think) that whereas other paintings by Bosch more or less explicitly warn the viewer of the sinful character of what is represented (like the ‘cave cave dominus videt’ in the Prado Tabletop), in the case of the Garden the viewer has to find out about this on his/her own and should not erroneously think that what he/she sees is ‘good’ because it has been painted in such a beautiful way.

The first two sections of chapter 8 also deal with the Garden, but they only offer a rhapsodic series of elaborations (i.a. on Nature’s and artists’ capacity to create novel things, on the probable commissioner and later owner of the Garden Engelbert II of Nassau and Henry III of Nassau and their Brussels palace, and on Jan Gossart). There is nothing here that brings us any closer to the centre panel’s deeper meaning, except for one short passage on page 233: ‘Bosch’s Hell panel does place a bold question mark after his image of a garden of delight. But it evidently has not sufficed to denounce the whole, since some viewers continue to take the center to be a positive statement about sex or marriage’. Thus, Koerner has given his personal answer to the question ‘are the paradisiacal pleasures shown in the centre panel sinful or not’ without producing too many convincing arguments. On the contrary, he is one more author who has succeeded in writing about the Garden’s centre panel without spending a single word on the group of three persons in the cave in the lower right corner. And we would also have welcomed an answer to the question of why there are black men and women in the centre panel.

-oOo-

Koerner’s Bosch & Bruegel is a beautiful book. It is written in an elegant and erudite style. It offers the reader a mixture of nice observations, of cultural-historical information based on a wide range of primary and secondary literature, and of often somewhat tedious or hard-to-follow elaborations. But when it comes down to a correct understanding of the world of Bosch, it is – in my opinion – certainly not impeccable. For a discussion of Koerner’s approach to Bruegel, I refer the reader to Ilsink’s review.

Other reviews

[explicit 1 February 2021]