Limentani Virdis 2010

“The crucified female Saint in Venice” (Caterina Limentani Virdis) 2010

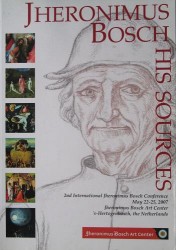

[in: Eric De Bruyn and Jos Koldeweij (eds.), Jheronimus Bosch. His Sources. 2nd International Jheronimus Bosch Conference, May 22-25, 2007, Jheronimus Bosch Art Center, ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands. Jheronimus Bosch Art Center, ’s-Hertogenbosch, 2010, pp. 232-242]

It is highly probable that Bosch’s triptych with a crucified female saint was in the possession of the Venetian cardinal Grimani in 1521, as can be derived from a contemporary reference to the painting by Marcantonio Michiel. The cardinal may have acquired the triptych through the Jewish publisher and merchant Daniel van Bomberghen, who was from Antwerp but resided in Venice. Grimani’s personal doctor, Abraham de Balmes, was also a Jew. Grimani’s contacts with the Jewish circle in Venice testify of his religious liberality and this may explain why he accepted as part of his collection an eccentric painting as that of the crucified female saint, whose subject was probably unknown to him.

Scientific technological research has revealed the presence of two donors on the side panels. Because of their clothing they have been deemed to be Italian and the crucified saint was thought to be Italian too: Saint Julia. Others believe the saint to be Saint Wilgefortis. As for the side panels recent studies suggest that they have been adapted to accompany the central panel and that they are slightly older than the central panel.

Limentani Virdis then focuses on the interpretation of the saint as Wilgefortis, which according to her is a northern corruption of the Latin Virgo Fortis (strong virgin). This name is related to the concept of the Mulier Virilis (manly woman), used for female martyrs and holy women rejecting their sexuality. Bosch’s female saint, having a masculine beard, is such a Mulier Virilis. If we accept this interpretation, many aspects of the painting’s iconography become less obscure. The triptych also shows some links with the theatre and particularly to passion plays. The man at the foot of the cross has not fainted, he is dead (close to him a pit is ready). Limentani Virdis identifies this man as the saint’s fiancé and as Christ, because in one version of the Wilgefortis legend the saint wants to affiance herself to Christ and that is why her father condemned her to the same martyrdom as her divine fiancé. The whole representation of the triptych could refer to a supposed mystery play of the legend of Wilgefortis.

It is also possible that the Wilgefortis legend mirrors the story of another disguised woman, Pope Joan. The theme of Wilgefortis was connected to that of the Female Pope, which was used in pre-reformist circles as a pretext for religious polemic: Bosch wanted to deal with a very important problem of his times and apparently his interest was in Christ.

The arguments in this contribution are not always convincing, to say the least.

[explicit 29 juli 2012]