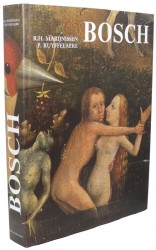

Marijnissen 1987

Hieronymus Bosch. The Complete Works (Roger H. Marijnissen with the assistance of Peter Ruyffelaere) 1987

[Mercatorfonds, Antwerp, 1987, 514 pages]

Some chapters of this splendid art book filled with numerous attractive pictures contains had already been published in Marijnissen e.a. 1972. This latter work only dealt with three Bosch triptychs (the Haywain, the Garden of Delights and the Temptations of St. Anthony) whereas now the complete oeuvre of the painter is being discussed. Marijnissen’s Bosch approach has not changed after all these years: Bosch is a religious moralist whose work may hide a number of magical elements but can best be grasped through a meticulous examination of the Brabantine environment to which he belonged. A lot of things in Bosch’s oeuvre are still unclear but then again: not everything is enigma.

The book’s structure is based on the outward appearance of the analysed works: first the triptychs and fragments of triptychs are presented, next the individual panels and the disputed attributions and finally the drawings. The first aim of this publication is to offer a status quaestionis of the research on Bosch which is why Marijnissen, when analysing a painting, lavishly refers to the results of the specialized literature on Bosch, even though these results often contradict each other. As one reviewer (Huvenne) pointed out, Marijnissen sometimes pays too much attention to extravagant interpretations and opinions that are no longer accepted. A nice example of this is the avalanche of confusing and contradictory interpretations of the Rotterdam Pedlar tondo, driving every reader to despair, Bosch experts as well as laymen [pp. 412-413]. On the other hand it must be admitted that Marijnissen properly succeeds in making his readers aware of the ludicrous proportions writings about Bosch (printed black on white) sometimes adopt. At the same time the reader can enjoy the author’s typical, aphoristic writing style when by means of one short sentence and with seemingly diabolical pleasure he once more outplays another art historian who is going astray. After having quoted ten lines from Wilhelm Fraenger referring to the church father Ambrose and dealing in a far-fetched way with the octagonal shape of the Rotterdam Pedlar tondo (which was probably sawn up centuries after Bosch died), Marijnissen just adds: ‘If the octagonal shape is the result of later sawing, we can forget Ambrose’ [p. 413]. In this way, thanks to Marijnissen’s wit and irony, the sometimes rather tedious summaries of earlier interpretations turn out to be anything but boring.

To these summaries the author always adds his personal opinion about iconographical, stylistic and technical issues. In doing so he keeps emphasizing the need for a meticulous technical examination of the complete Bosch works. When dealing with problematical iconographical details he often wisely keeps his distance or suggests a direction for potential further research. Sometimes he elaborates on a hypothesis of his own, based on texts and illustrations in lesser known late-medieval books and manuscripts. These personal contributions to Bosch’s iconography are by no means the least interesting parts of this publication.

Sometimes Marijnissen makes a little mistake, but these moments are very rare. When on page 302 he writes that the Earthly Paradise wing (one of the four preserved Last Judgement wings in Venice) bears a wrong title because this subject seems to be ‘out of context’, apparently he is not aware of the medieval view according to which the Earthly Paradise functioned as a waiting room for the souls before they could enter Heaven. Another flaw is the absence of Dirk Bax’ posthumous book (1983) in the bibliography. But these are only minor points of criticism. As a whole this monograph is a genuine and reliable work of reference reaching a quality seldomly encountered in the literature about Bosch.

This book, originally published in Dutch, was translated into French, English, German, Spanish and Russian. In 1999 an identical reprint was published (Marijnissen 1999) followed in 2007 by another reprint to which a foreword by Jos Koldeweij, some illustrations and an appendix summarizing the Hieronymus Bosch research since 1985 were added (Marijnissen 2007).

Reviews

[explicit]